Kinship With Kingfishers

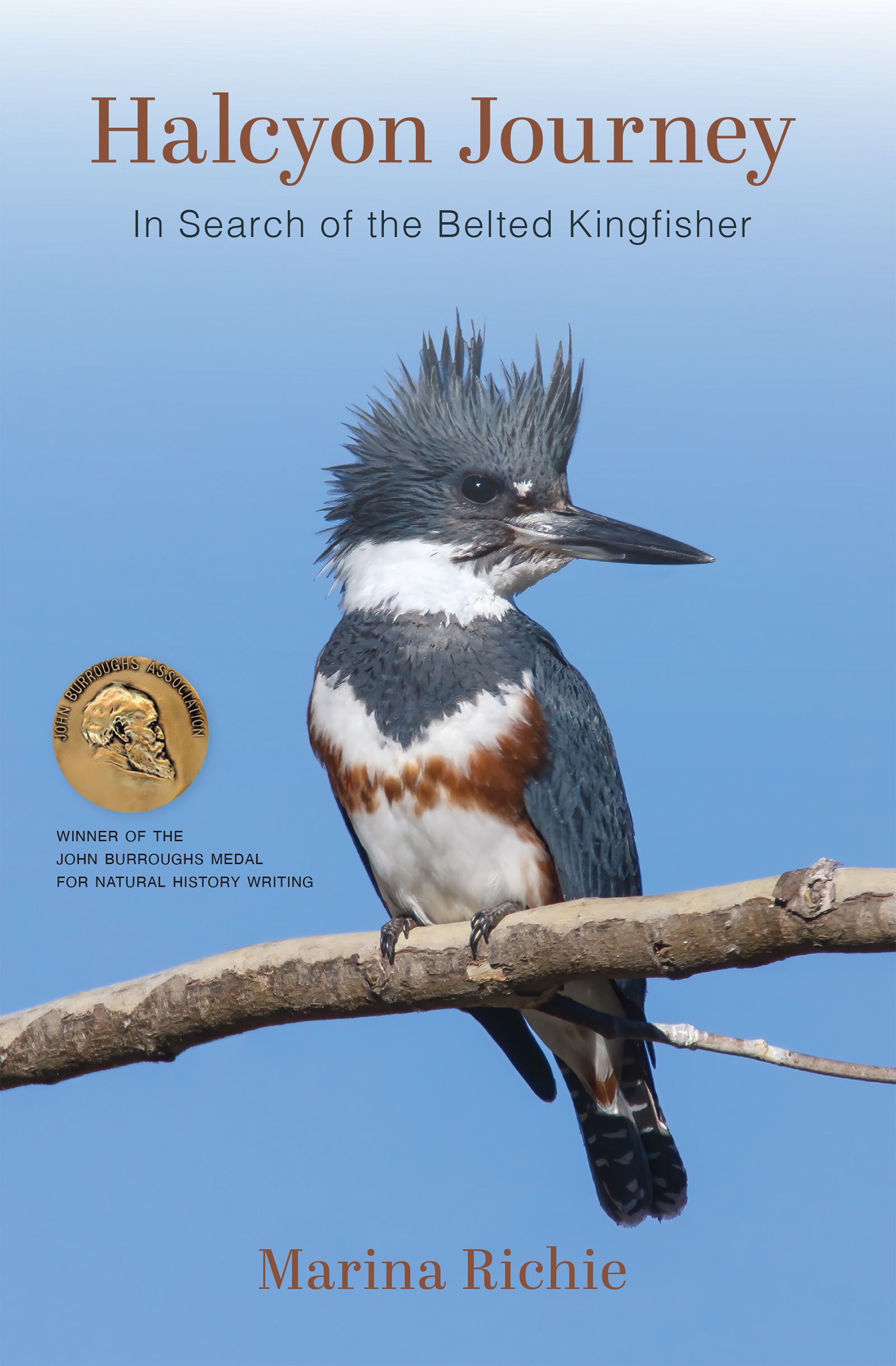

“I believe our kinship with all life is at stake. Unless enough of us spend time in the field immersing, noticing, reveling, and wondering, we won’t act in time to save ourselves. We don’t have to be biologists; we only have to be curious.” – Marina Richie, Halcyon Journey, In Search of the Belted Kingfisher

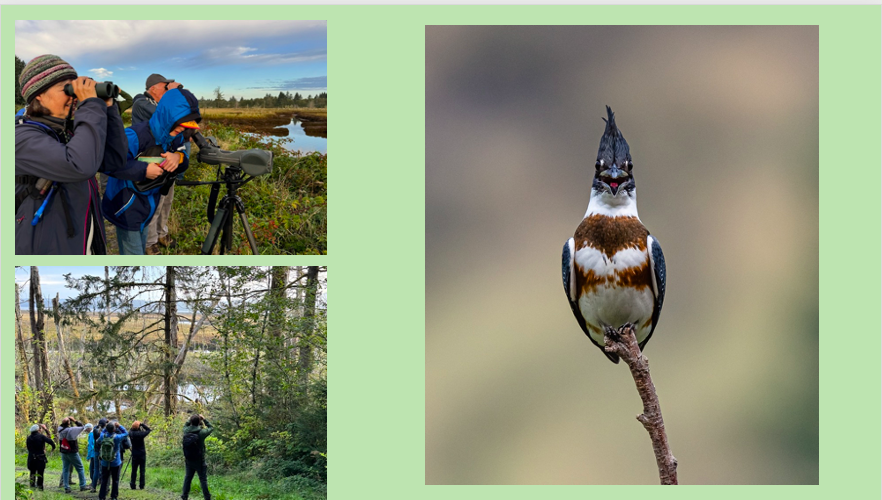

On the cusp of the autumnal equinox, I had the pleasure of giving the keynote speech –“Kinship with Kingfishers”– at the Wings Over Willapa bird festival on the Long Beach Peninsula of southwest Washington. Brown Pelicans sailed the Pacific waves–riding a cushion of salty air and plunge-diving with those bucket beaks to scoop up fish. On the bay side, high tinkling notes of Golden-crowned Kinglets ringed the candelabra canopies of ancient western red cedars saved from the chainsaw on Long Island and Teal Sough– protected within the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge.

And yes…a female Belted Kingfisher hovered above Tarlatt Slough as a river otter popped up from reflecting waters to gaze at our birding group in whiskered curiosity. The kingfisher’s cinnamon-red belt signaled–Queenfisher! A boy named Shepherd gazed through the spotting scope when she perched briefly on a refuge sign in the marsh. A juvenile Northern Harrier skimmed the grasses with easy flaps and glides.

Shepherd’s father and grandfather were there as well– three generations sharing a love of birds. Shepherd carefully printed the names of certain birds in the lined pages at the back of a bird book he clutched in his hands.

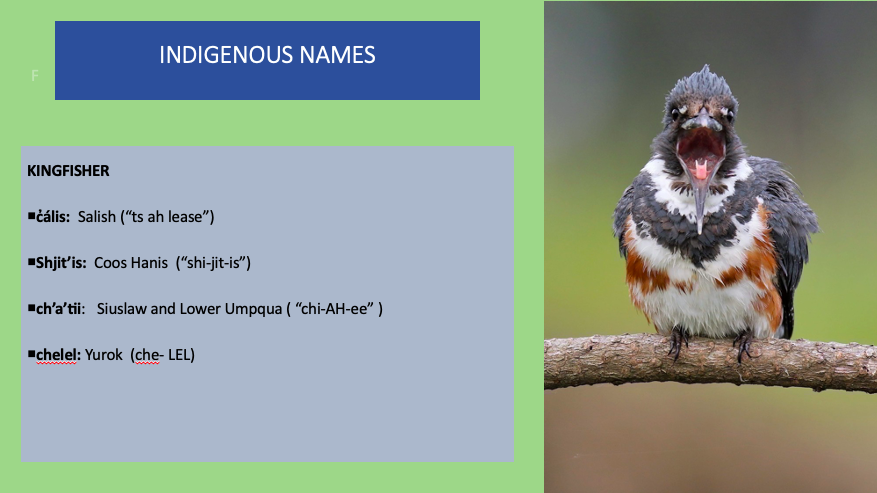

Kinship. Grandfather-father-son-birds-water-kingfisher. To identify is the first step to knowing. In my talk, I shared Indigenous names for the Belted Kingfisher and called for ways of naming that are immersive in nature. Try speaking these kingfisher names with the phonetics- TS ah lease. Shi-JIT-is. Chi-AH-ee. che-LEL. I hear rushing water, the repeated consonant snaps of a kingfisher call, the purling of tidal waters, and the tranquil state of happiness among bird-filled waters and interwoven shorelines.

In my journey of seeking, losing, and finding kingfishers on a then-home creek in Missoula, Montana, I entered a wild community the Salish people have known since time immemorial. More than a decade ago, I listened to Salish elder Louis Adams speak by the banks of the Shimmering Cold Waters (translation for Middle Clark Fork River flowing through Missoula). In my book, I described his words this way: “Listening to Louis intersperse English with Salish words, I noticed how the language was at once guttural and melodic in the dynamic way of a homeland shaped by fires, floods, and winds.”

Isn’t it time to embrace a language of kinship? To reject calling the other-than-human world by the objectifying pronoun “it”? We could embrace Robin Wall Kimmerer’s call of “ki” for an individual and “kin” for plural when we don’t know the gender. In revising my manuscript before publishing, I went through every use of “it” and figured out ways to avoid the pronoun. Today, I also write poetry without “it” and feel the bond with nature strengthening line by line, stanza by stanza.

Names matter. And just as nature is dynamic, from branch-breaking windstorms to lightning-kindled fire, so is language. I commend the American Ornithological Society for the decision to change more than 200 bird names in North and South America that refer to people–from Cooper’s Hawk to Steller’s Jay. We can adapt. We can participate. There will be a time of transition. The movement started with a recognition that some names have racist origins, like McCown’s Longspur (John McCown was a Confederate general). I applaud that beginning and the first change –Thick-billed Longspur.

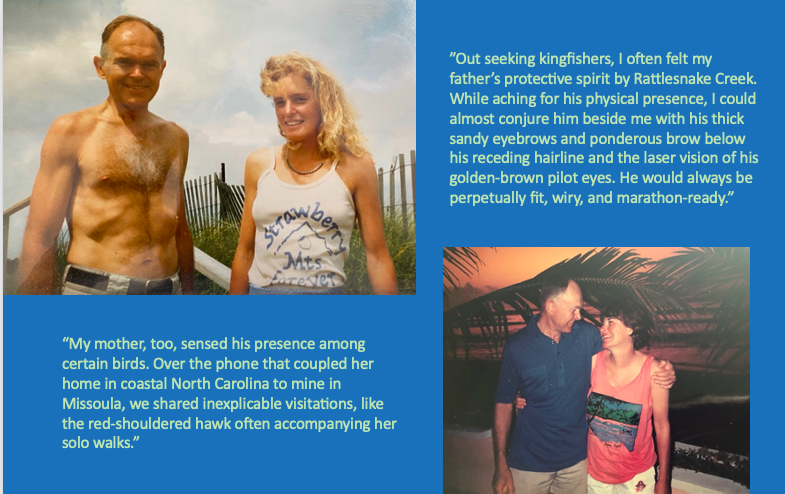

As I cheer for names that tell us more about a bird and reflect humility and respect for the natural world, I also understand a desire to honor a loved one. Perhaps we do that quietly. When a Swainson’s Thrush flutes his spiraling melody into treetops, I sometimes whisper to my father Dave Richie, who gave me a silver flute when I was 13 and loved all thrush songs.

I touch a white blaze on a tree on the Appalachian Trail and thank my Dad for all he did to preserve the Trail as A.T. Project Manager for the National Park Service. In his era, he oversaw major land acquisitions for a connected footpath of almost 2000 miles with a land corridor, which has become an essential skyway for birds and passage for wildlife moving north in a warming climate. Do I want him to be remembered publicly? Absolutely. But there are other ways than naming a place in nature for him. For example, there’s a Dave Richie memorial bench by the A.T. headquarters in Harpers Ferry (thanks to A.T. hero Steve Golden and others who worked side by side with my Dad in that golden era of the 1970s and ’80s).

Kinship with Kingfishers. I watch the hover above gleaming waters and time is suspended. All else falls away in present wonder. Even sorrow flees with every feathered wingbeat. In my talk, I shared the healing power of all those hours, days, and months under the spell of kingfishers on Rattlesnake Creek, only blocks away from home.

Fueled by an obsession for this bird, by curiosity, and yes–love, I was out by the creek in predawn, in spring blizzard, wind, rain, hail, and heat. Once, a mink shimmied across my bare legs as I sat still on the creek’s edge on a warm fall day with no real purpose, except to be in my happy place on a halcyon day.

My parents are not here with me physically, yet I find kinship with them in nature and in birds. Right after my mother died in June of 2020, I saw a kingfisher lift from the pond outside her room at the Collington retirement community in Maryland. My tears mingled with the rain and the flash of wings vanishing around an island.

Close to the end of my talk before that wonderful audience at Wings Over Willapa bird festival, I asked everyone to close their eyes and envision a place where they felt intimate and connected with nature. Kinship. I invite you to do the same…and maybe add the rattle of a kingfisher trailing away.

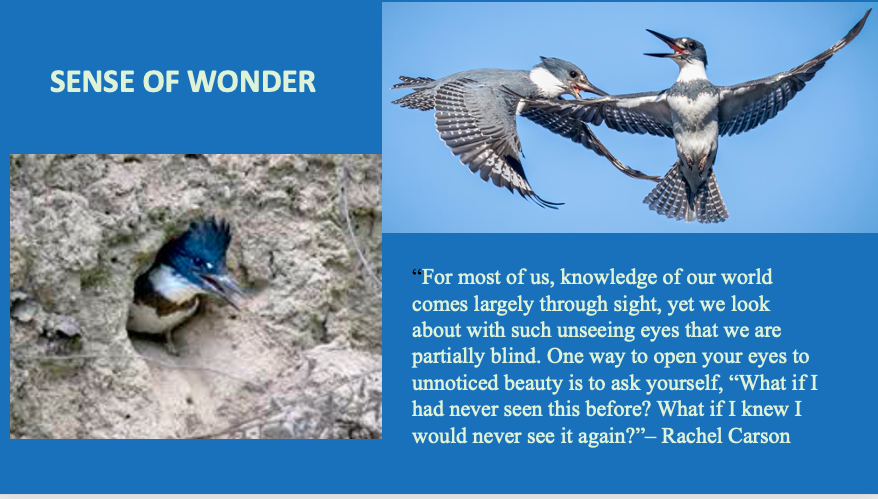

Finally, there’s an image I will never forget of a young kingfisher peering out from a nest hole into that big sunny, bird-spun world after a month tucked safe in a burrow at the end of a tunnel. Sense of wonder! Rachel Carson wrote those lasting words in 1956. Remember her, too. Say her name. For Rachel, speak up on behalf of all who cannot raise their voices in the human world. Vote in November for the future of wonder.

I dedicate this blog to my friend Douglas Schoen, who passed away in late July of 2024, from injuries after a fall while hiking. Thank you Douglas for your inspiring advocacy on behalf of Wilderness that resulted in the Middle Santiam Wilderness–an ancient forest sanctum in the Oregon Cascades. Thank you for your way in this world–gentle, elegant, kind, and generous. I promise I will do what I can on behalf of saving Wilderness, wild trees, wild rivers, wild birds…always in kinship.

Your Last Forest

For Douglas

Before you tumbled

down a rocky ravine

when the forest shattered

into a kaleidoscope

of ferns, lichen and pain,

you inhaled incense

of cedar, fir, and maple

as chickadees bantered,

while plucking caterpillars

from limbs to feed

their chicks.

Walking the trail

with gentle footfall,

senses attuned

to beauty coursing

through your veins

like a waterfall

you knew only… joy.

— Marina Richie

Eyes closed …. my hyper active and wandering mind flitted back and forth like a Kingfisher looking for that perfect perch over the river.

As it peers through the viewfinder … mind wanders up and down and to and fro … flashing from a Greater Sage Grouse nipping a tender tasty sage brush leaf in the high sage steppe … then suddenly hearing the rattle of a Kingfisher soaring to a perch over the Boise River before arrowing into the cool clear water to nip a silvery morsel!

A wonderful collage of God’s creatures in their places that cry out for our stewardship in a rapidly warming and changing world.

cont’d

Friend, Mike

Beautiful, Ken….I was right there with you flitting from sage grouse to kingfisher….love the way you connect the two birds of such wildly different habitats–with that word “nip.”

I was inspired by a Kingfisher photo (the one the top of the blog) and a Greater Sage Grouse looking at me from their frames on my wall by my computer 🙂