A Kingfisher Runs Through It

“You can love completely without complete understanding.”—Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories

When I give presentations on Halcyon Journey, In Search of the Belted Kingfisher, I often speak of the kingfisher as a messenger calling for us to care for precious waters from headwaters to the sea. The staccato notes cut through all static with the clarion reminder—water is life. Honor complex ecosystems that filter and purify waters, slow floods, protect drinking water, and naturally capture and store carbon. Be humble in the presence of a greater wisdom than ours.

That theme resonated more strongly than ever in my recent nine days in coastal North Carolina, a trip of memories and of connections with good people heeding the kingfisher message—saving the Magnificent Ramshorn snail from extinction; conserving a family farm and woods on the Albemarle Sound; and standing up to stop the clearcutting of wetland forests thick with oak, hickory, beech, sycamore, poplar, gum, pine, and cypress, dripping in biodiversity, and with great power to protect the planet.

Kingfishers threaded every day. Enlivening calls spiced fiery sunrises over fish-rippled waters of the Intracoastal waterway, not far from where my parents had once lived in Hampstead (near Wilmington). One morning I strolled barefoot around Serenity Point of Topsail Island as a small flock of sanderlings skittered the line of wave and sand. A dolphin arced from bay waters. My parents’ spirits entwined where they had once walked hand in hand. Memories.

At Greenfield Lake in Wilmington, two male belted kingfishers swerved, pivoted, and chased in a riveting aerial contest of territory. A third kingfisher at the far end staked out a post on a boat launch and dove repeatedly into the chilled waters. Once, she skimmed low enough to wet her breast feathers and fly back up to preen her gleaming plumage. Mingling with a group of local Audubon birders led by Jill Peleuses of the Cape Fear Bird Observatory, I found camaraderie among those who delight in every bird and seek hidden recesses of habitats.

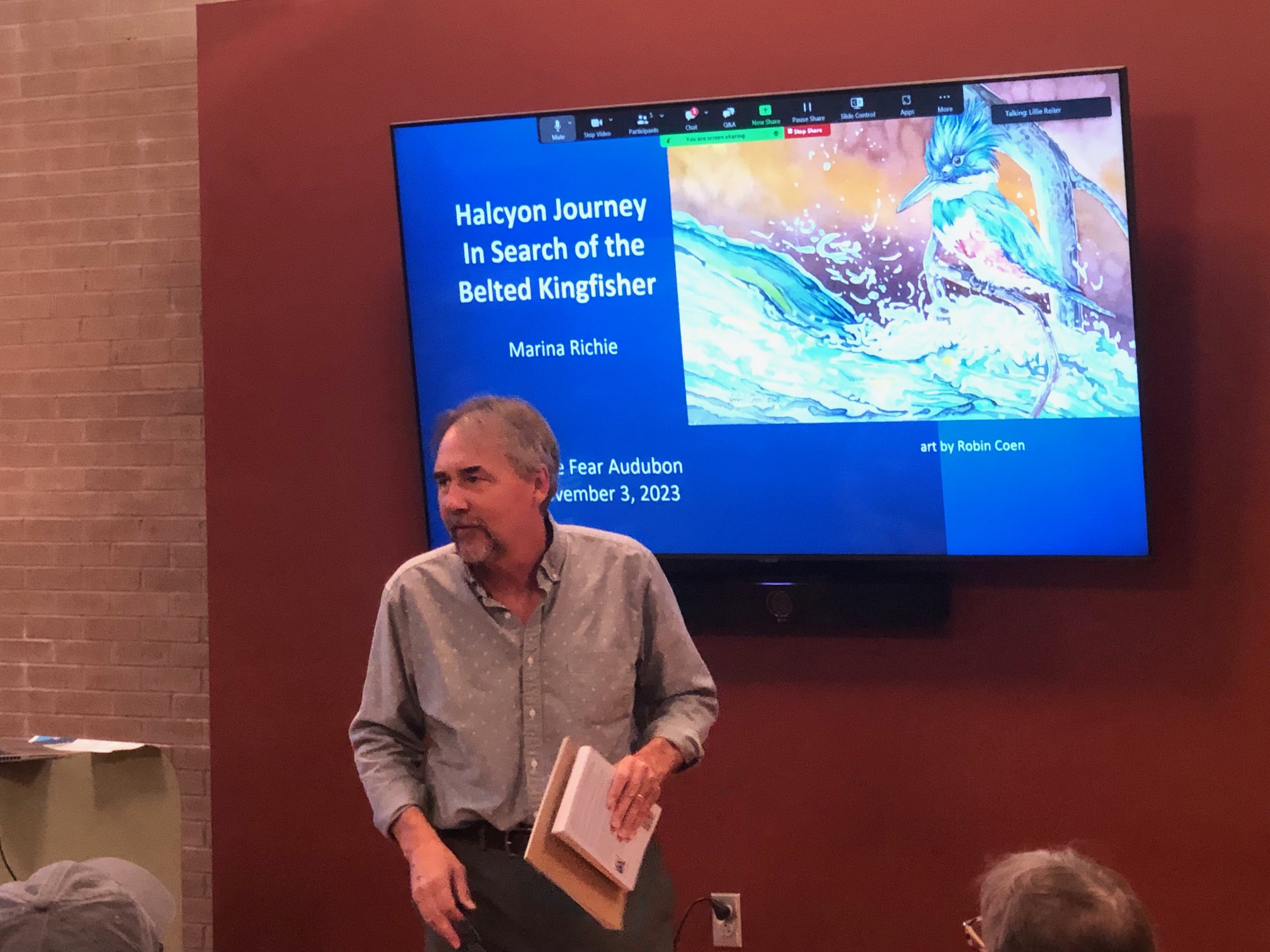

When I spoke before Cape Fear Audubon on the evening of November third, I felt buoyed up by a room full of kingfisher aficionados. My kin. At last, I also met author David Gessner who gave the introduction. We shared a laugh at my story of me sending him an email asking for his ideas for the book I’d hoped to write and his response—nine years later.

Gessner’s early book Return of the Osprey inspired my quest to follow kingfishers in ways not possible with a quick dip into their lives. His newest book, A Travelers Guide to the End of the World, Tales of Fire, Wind, and Water is a sojourn of witness and urgency. Waters that kingfishers know swirl throughout his book on the climate crisis—drought, vanishing aquifers, taking too much and giving back too little, and the ferocity of relentless ocean rise, extreme hurricanes, and flooding, even as people continue to build mansions on barrier islands. Yet throughout, he holds up the messengers, the doers, and those who show us a better way.

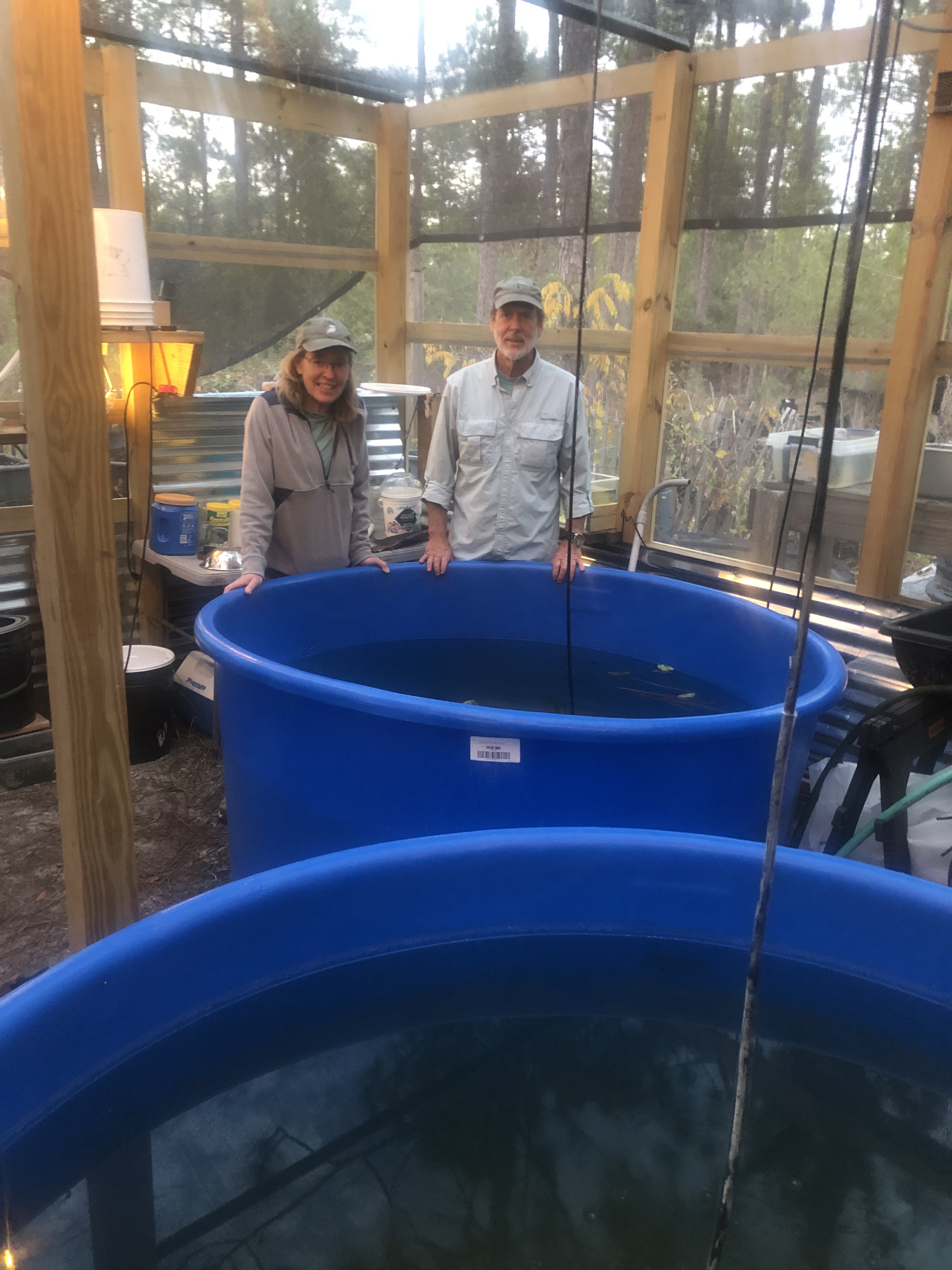

I met many changemakers in North Carolina, thanks to my host and tireless environmentalist Jack Spruill. I also reunited with a family friend—the naturalist Andy Wood, saver of the Magnificent Ramshorn snail from extinction and articulate advocate for the threatened wilds of North Carolina. Just this past week, the first of these imperiled snails returned to the wild in a hidden pond in Brunswick County. Read about Andy’s magnificent rescue of the snails in the midst of Hurricane Fran.

One morning, Andy and I walked a birding trail on the Northeast Cape Fear River lined with reflecting autumnal forests to visit a bald cypress maybe 800+ years old with a black hollow in the base, a tree my father knew well. Feeling a sense of his spirit at that place, I nodded to the belted kingfisher winging along the river—giving voice to the voiceless.

In the middle of my stay centered in the Hampstead/Wilmington area, I spent two and a half days some 180 miles northeast of Wilmington in the Plymouth, Roper, and Edenton area of the Albemarle Sound. This was a long anticipated trip with my Hampstead host Jack Spruill to wander his family farm, woods, and waterfront. Jack is in the final phase of donating the Spruill Farm for permanent conservation and education. There, I met the energetic couple Julia Townsend and Lincoln Adams who are carrying out and building upon his vision (another story to tell).

The afternoon we arrived, Jack guided me through a 12-acre separate wooded tract of the 110-acre Spruill Farm–introducing me to trees he knew as individuals and friends. Bald cypress sprouted knees by Kendrick Creek. Thick black vines snaked up powerful southern red oaks. I peered through the hollow base of a Tupelo gum and leaned back to look up through leafy canopies spun gold and green. As we wandered among the dizzying array of tree species, a pair of barred owls duetted from high above us in a searing ricochet of wild calls. The message I chose to hear was this: “Save the forests of the southeast!”

I’d also entered a region within a 50-mile zone of forest destruction to feed the insatiable wood pellet plant in Ahoskie. This is ground zero for environmental injustice to a vulnerable community living with choking dust, noise, and pollutants emitted around the clock. The story of Ahoskie is repeated at the 10 Enviva plants in the southeast to the drum of greenwashing on the company’s website.

The facts alone are shocking. Enviva is responsible for clearcutting thousands upon thousands of acres of natural hardwood and pine forests (not plantations) to be chipped for wood pellets, which are then shipped overseas to the UK to be burned by the company Drax as energy—releasing far more carbon into the air than coal, as the UK claims the false “green” energy as lowering emissions. The entire European Union, with the exception of Australia, is complicit. Asian markets are booming, too, especially in Japan and South Korea.

While I was there, Enviva’s stock crashed and the house of cards fell. In this flickering moment of celebration, there’s also the sobering knowledge that if Enviva fails, another company might step in to feed the highly subsidized biomass industry. But there are signs the tide is turning overseas and here as climate activists learn the truth from Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), the Dogwood Alliance, the Coastal Plain Conservation Group, and the heroic efforts of other groups and individuals—some featured here in a recent five-minute video, “Burning the Future.”

From afar, I’m supporting the fight to save the southeast forests and helping to raise the alarm in Oregon about the threats of all biomass industries. However, to stumble over the crushed remnants of a once vibrant forest is to become intimate with human-caused devastation. I saw only one black butterfly fluttering across the 200-acre clearcut that a month ago brimmed with irreplaceable plant and animal lives. The contrast between the protected Spruill Farm woods and this devastation could not have been more stark.

Bearing witness to the killing of natural forests of stunning biodiversity left me bereft. I felt immense despair in this graveyard. There is no renewal here. And yet, I did find a way of renewal in the presence of our guide that day– a photographer who is taking risks to follow chip trucks to the Enviva mill and to active clearcutting where whole trees are shoved into chippers. He’s exposing the company’s lies with on-site photos and drone imagery.

I’m in awe of the activists who are speaking up, showing up, and applying their passion and talents to stop the madness and advocate for wild forests and natural ecosystems that are critical to the future of life on our planet.

On this Thanksgiving, my heart fills with gratitude for the North Carolina environmentalists. When I turn to my efforts on behalf of Oregon wilds, I feel far from alone. We are like the mycelial network of a great forest with vast root systems interlinked, communicating, and giving one another strength. We are messengers heeding the rattling cries of belted kingfishers across North America.

#

“We can continue pushing our earth out of balance, with greenhouse gases accelerating each year, or we can regain balance by acknowledging that if we harm one species, one forest, one lake, this ripples through the entire complex web. Mistreatment of one species is mistreatment of all.” — Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree, Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.