Driving Home in the Arctic Freeze, I Hit a Songbird

Driving well below the speed limit, I took a day and a half to cover the 600 miles between my former community of Missoula, Montana, to my home in Bend, Oregon. I reveled in the turtle speed relative to the hurtling trucks and the few cars out in the bitter Arctic blast. Going slower meant I could attend to ice on bridges, packed snow on the mountain passes, and other drivers.

What a joy to be unhurried in my passage, even as my environmentalist mind reprimanded my double standard of fighting fossil fuels while filling up my tank. I took some comfort in the improved gas mileage from slowing down and knowing I could be more careful in avoiding animals unlucky enough to venture onto the highway.

Looking out from the warmth of my small pickup truck cab, I noted the slow flaps of a Bald Eagle headed toward the Clark Fork River muffled in an icy shroud. A Rough-legged Hawk (denizen of the far north come south for the winter) perched on a telephone pole. Ravens exulted in the frigid air–black wings sweeping crystals into vortices. It was minus eight Fahrenheit when I left Missoula this past Sunday, far more benign than minus 22 the morning before.

Birds fluffed their feathers into airy insulated cloaks. In Missoula, frost tipped the lush thick winter pelage of Rocky Mountain elk on Mt Jumbo. When I had walked outside bundled in layers, my eyelashes froze. I breathed through a scarf and felt the relentless cold seep in with every step.

On day two of my homeward drive as I steered south of the Columbia River on Highway 97 toward Bend listening to the engrossing book Better Living Through Birding, Notes from a Black Man in the Natural World, by Christian Cooper (narrated by the author), I was feeling especially tender toward birds. The audiobook features songs at the start of each chapter–twitters of Chimney Swifts and the heart-quickening ephemeral notes of the author’s favorite, the Blackburnian Warbler.

Here, snow-covered sagebrush interspersed with wheat fields and frosty lone trees. I’d noted small flocks of sparrows too hard for me to identify even at a slower speed. I was sure Christian Cooper would know them by flight pattern and silhouette. If not, he’d pull over and sleuth out their species no matter what temperature. I considered, but did not see a pullout. The songbirds were gathering at the roadside to peck at gravel–ingesting pebbles to aid digestion. Sometimes, they flew into the hazy sky in a swirl of winged stones.

A flock of about seven burst into the air and flurried right in front of the truck. One bird struck my windshield. I cringed, ducked instinctively, and held the steering wheel tight without a swerve. Thud! Bounce! Gone. Only a single ashy gray downy feather tinged in cinnamon clung for seconds to the glass. Cursing myself for not anticipating and braking (safely), I realized that in the cold, birds likely fly slower. Blinking away tears, I vowed to do better. Within five minutes I had my chance.

A Rough-legged Hawk veered right toward the truck’s passenger side and this time I did brake–not hard, but enough. The hawk was fine. I breathed a little easier, yet uneasy.

Our gas-guzzling driving habits are not only killing life on our planet, but also directly killing wildlife–as all of us know from dead animals on and alongside roads. Have we become numb to the dying? Do we excuse ourselves too easily? One solution is to be part of the activism that has led to more overpasses and underpasses for safe wildlife crossings. All of us should support measures to help wildlife navigate our deadly roads. On my list of books to read on this subject is Ben Goldfarb’s 2023 book: Crossings, How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet.

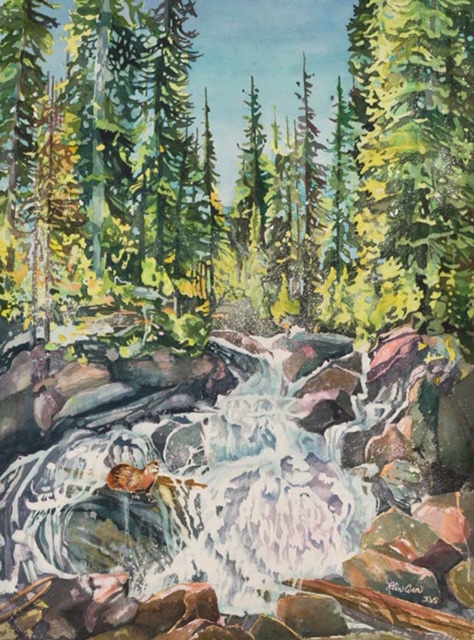

I do not regret the trip. To spend two weeks in Missoula with my son Ian and dear friends and to re-immerse in Rattlesnake Creek of kingfishers renewed my spirit and reconnected me to a precious pocket within a vast Northern Rockies ecosystem.

I did not fly on a plane. I saved fuel with conservative driving. I camped on the way over. But there it is. Each time I stopped to fill up gas, I winced. At least at home, we have a Prius and I hope to switch to an electric vehicle. I want to engage in more ethical ways of travel.

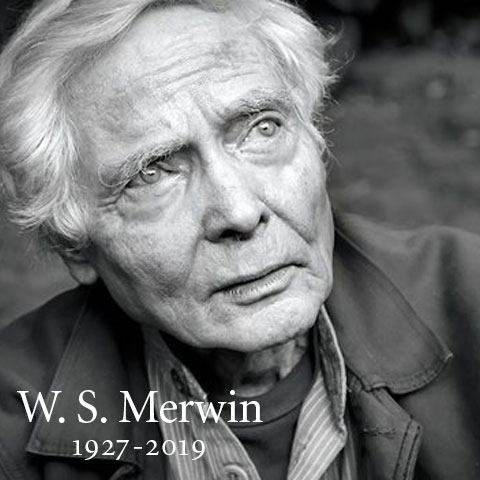

I remember an interview with the great late poet W.S. Merwin who articulated how he grappled with living each day celebrating the beauty of nature while participating in our human destructive ways. He was not at ease either, yet he lived more simply than most and rewilded his Hawaii home ground. His poetry on behalf of the earth could be fierce.

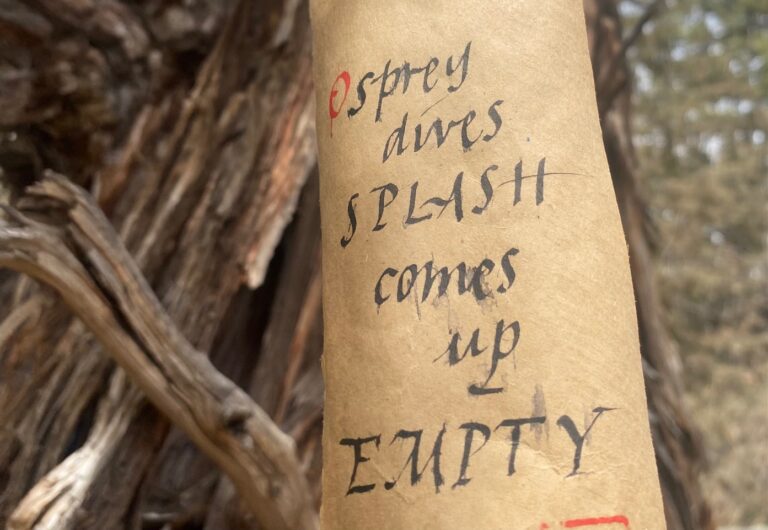

For what else will shake us awake? From Merwin’s “For a Coming Extinction” the first lines are chilling: “Gray whale, Now That we are sending you to The End…”

I’m perusing his poems this morning as I write with winds fleecing the pines of their snow. On the Merlin Conservancy website, I come upon “Rain Light.” Yes. This one. I look up an interview with Merwin about the poem. He begins by saying that living in this time where the world as we know it is dissolving around us and all is endangered, we have a choice to either face our moment or groan and dread it. He chose the former, while keeping us buoyed on his poetic updrafts like soaring raptors– reminding us of the gentle touch of dawn rain, the entwining of life and death in a cycle, and a way of entering each day fresh-faced and open to beauty.

On this day with the sadness of the sparrow’s life cut short still heavy on my conscience, I offer Merwin’s poem and a reminder of being present and connected to the other-than-human world. Out my window now as rain falls on deep snow in our yard, Dark-eyed Juncos peck seeds on the shoveled path When they fly, their dark tails flash white outer feathers, a distraction display to baffle hungry Cooper’s Hawks and Sharp-Shinned Hawks. They live exposed to the elements, alert, and bright-eyed. I wonder. Do they “wake without a question?” They cannot know what we have wrought with the climate and biodiversity crisis upon us. It is our time to act–strengthened by the community of so many like-minded people who wake each day with gratitude and wonder.

RAIN LIGHT

All day the stars watch from long ago

my mother said I am going now

when you are alone you will be all right

whether or not you know you will know

look at the old house in the dawn rain

all the flowers are forms of water

the sun reminds them through a white cloud

touches the patchwork spread on the hill

the washed colors of the afterlife

that lived there long before you were born

see how they wake without a question

even though the whole world is burning

— W.S. Merwin, from his Pulitzer-Prize winning book The Shadow of Sirius (Copper Canyon Press, 2008).