Heart Beats of Ancient Bald Cypress

A North Carolina kayaking journey leads to an inner sanctum of bald cypress trees living for more than 2,000 years.

Paddling the Black River, I enter deep time measured in tight rings of slow-growing bald cypress. Our single kayaks form a festive flotilla on dark polished waters. On this early May morning, sunshine splashes through clouds like Prothonotary Warblers flashing yellow plumage.

Captain Charles Robbins (nicknamed C.R.) leads us on a 12-mile downriver trek from Henry’s Landing, about 40 miles inland from the North Carolina coast. About halfway, we will linger in the Three Sisters Swamp, protected by The Nature Conservancy as a key part of the Black River Preserve. C.R. knows the river’s twists and turns, rise and fall of waters, and shifting sands. Each year, he guides hundreds of people in small groups–sharing reverence laced with ecology and humorous anecdotes.

A native of the Cape Fear River area, C.R. has spent days and nights with the elder trees, sleeping in a hammock as bats nip insects at dusk. He’s led journalists, filmmakers, scientists, and environmentalists into hidden recesses and helped age cypress with Dr. David Stahle of the University of Arkansas Tree-Ring Laboratory. As an advocate for ancient bald cypress preservation, he heads the steering committee for Friends of the Black River North Carolina.

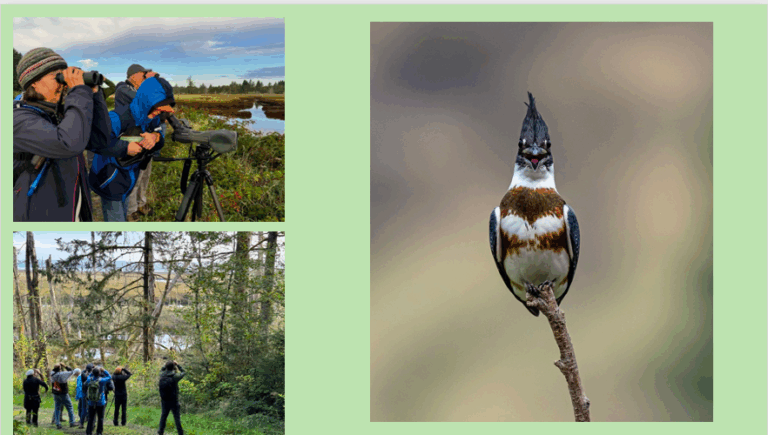

Holding my kayak paddle in a loose grip, I reach forward to dip my right blade and lever with my left hand. Pull through water, lift and then repeat on the left. Awkward at first, I aspire for fluidity. I’m struck by the shimmering leafy diversity of hardwood trees mingling with cypress so wedded to water. Often, I raise my binoculars and drift sideways, falling behind to learn the birds from Howard Ferguson, a retired wildlife biologist with a keen ear.

Soon, I’m discerning the spark-bright tweets of a Prothonotary Warbler, the ascending trill of a Northern Parula Warbler, the buzzy vibrato of a Great-crested Flycatcher, and a Yellow-throated Warbler’s clear falling notes with an uptick ending. Our youthful assistant guide Eric stays back, too. He has a gentle knack for herding stragglers, along with other talents like African drumming on cypress knees.

Kingfisher? Rounding a river bend, we come to a long high bluff of layered diggable soils. I’m on the alert for a Belted Kingfisher nest hole. I snap photos of a couple of tennis-ball-sized nest holes–one with a telltale twin furrow at the base and the other with a cascade of fresh soil below. Which one is the real burrow? Never do these birds share a nest bank with another pair. As always, kingfishers remain a gift to see. On this day, I will not hear the familiar “Kkkkk! Kkkk.

Toward midday, C.R. turns his kayak into a tangled narrow passageway. Cypress knees rise up from reflecting waters like knobby fingers of giants. In places, we hop out of our boats to pull them over shallow sands. Rounding sharp bends around trees, we are told to paddle hard. Anticipation builds. We are getting closer to the sanctum.

Arrival. We slide kayaks onto a small beach among the oldest cypress. A single Prothonotary Warbler perches on a tree knee within a few feet of our group, tilts his head back and belts out a solo. He flies to another until we are ringed in music. C.R. tells us this bird has a nest nearby in a hole within a cypress knee. Our chorus of human voices chirp in bursts of wonder….fairyland…primeval…Jurassic Park…Amazonian….magic…

Beaching our kayaks, we slosh knee-deep through cool tannic waters pooling over sand. The light is tinted in spring greens. Sunlight recedes into clouds. Common Nighthawks circle high above the trees pursuing aerial insects and giving their haunting peeent calls They are conjurers of darkness in midday.

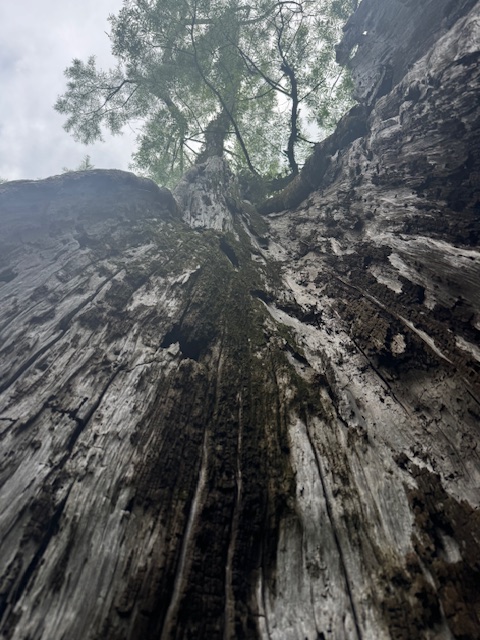

We’re spellbound and unbound from our short lives. It’s as if we’d hurtled back through a time portal to the Upper Cretaceous when modern cypress first appeared within an epoch that lasted from 100 million to 66 million years ago, the heyday for dinosaurs before extinction.

C.R. wades to show us the oldest recorded living bald cypress at 2,626 years, and recorded only in 2018. To find a solid core, dendrochronologist David Stahle climbed ten feet up a ladder to hand drill a tiny hole with an increment borer, which extracts a pencil-like sample showing every ring. Nearby trees may be closer to 3,000 years or even older, yet they hide their age in hollowness.

We linger over lunches and wander among reflecting waters. Marvel at the gray striated bark of trunks and burls on trunks. Peer through a gaping mouth into the cave-like trunk. Ponder cypress knees and interweavings of a forest withholding her secrets. Gasp at a cypress split vertically yet still growing as a mossy wall roofed in fine branchlets netted in green.

Tree Teachers. What is it to thrive through droughts, floods, and hurricanes not for centuries but for millennia? The oldest trees of the preserve are paleoclimate storytellers. The scientists are listening. The trees challenge all perceptions of “historic conditions” and may give insights on survival in our era of human-induced global warming and biodiversity loss. Surely, they are also warning us. Stop with all this hubris before it’s too late.

Rain. Clouds exhale waterfalls on feathery spring-green needles of water-immersed cypress–a deciduous conifer. Droplets became flocks. Rain pours like a kingfisher plunge drenching clothes and skin. Skin becomes the drum for rain fingers flying quick as Chimney Swifts. Darting after insects high above us, the arrowed swifts become a tremolo of thunder thrum. Their roosts are within cypress chimneys.

This is the world the bald cypress know. Dragonflies quiver transparent wings. Brown water snakes –harmless hunters of catfish–coil on cypress knees. A Great Blue Heron slow flaps past like time rumpling until the word “primeval” basks on our brows. Hollowed living cypress, with trunks like gourds and their heartwood long gone, carry the bass beats.

Continuing our downriver journey, we have not left the ancient ones behind or the ringing of birds or the sleeping snakes. I’m dazzled by wavering tree reflections, and one particular cypress with an immense round ball encircling the trunk 20-feet up. I want to fly up and perch on the mossy platform and look up the split open trunk.

In our last mile on a widening river, rain pours down. We are soaked yet jubilant. A rumbling truck ahead signals time winding forward to the present. Easing out of our kayaks below a bridge, we reenter our noisy lives with spirits cleansed. But first is the reality of a shuttle, where eight of us cram into a Subaru Crosstrek. We don’t mind. We’re like turtles piling on cypress knees. Intimacy. Laughter. Camaraderie.

Home. Back in Bend, Oregon, and writing of this tropical lost-in-time realm, I am contemplating the urgency of protecting all ancient and intact forests and migratory birds as powerful messengers. The future of the Prothonotary Warbler, for instance, is precarious–with losses of mangroves in coastal wintering homes of Mexico, Central, and South America as well as summer breeding homes in bottomland forests filled with big trees and dead trees with nest holes.

Less than one percent of the ancient bald cypress forests are left. Once cloaking 40 million acres of the southeast, 90 percent of the old-growth trees were felled by 1930 as durable wood for shingles, siding, ladders, fence posts, stakes, and water tanks. Beyond the logging, the U.S. Government funded draining swamps for farmland. Dams flooded the forests too. Habitat destruction led to probably extinction for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, and the vanishing of the Bachman’s Warbler and Carolina Parakeet. (Note–these birds lived to the south of Black River). Today, bald cypress closest to the coast are becoming ghost forests–skeletons killed by excessive salt from sea rise and other forces.

Yet, the inland Black River cypress escaped logging and draining, and so far salinity. While the Three Sisters grove is the sanctum, all along the 60 river miles are ancient trees. The ecosystem is mostly intact and a high priority for The Nature Conservancy–with 18,000 acres conserved so far. However, the Black River Preserve alone cannot fully preserve the oldest bald cypress on earth. Some forests remain vulnerable to logging. Water quality is at risk from massive hog farms in the upper watersheds.

Protect. How could we not permanently protect one of the great wonders of the world? We have work to do and still time to accomplish the task. An outstanding example is Congaree National Park in South Carolina–a victory that resulted in protecting the largest old-growth bottomland hardwood forests remaining. (See this 1975 New York Times article on 700 people rallying in South Carolina to preserve the Congaree –then threatened by logging). Activism resulted first in the Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976 with expansions and thousands of acres designated as wilderness. In 2003, Congress established Congaree National Park. While this may not apply to the Black River where the situation is different, I share the story for inspiration.

“Every place in this nation that is now safe for all of us didn’t just happen.” In that 1975 speech to activists who would save the Congaree swamp, Brock Evans (then the Washington office director of the Sierra Club) reminded them of their power. “It’s a force called love. Love for our earth. Love enough to fight for it. Love enough to never quit.”

I believe when I have the great good fortune to take a trip like kayaking into the Three Sisters Swamp, I have a responsibility to give back–through my writing, and support of the good people who are spending hundreds of hours of volunteer time to save our last wildlands and waters. I’ve just donated to the Friends of the Black River North Carolina. Right now, they’ve submitted a proposal to the National Park Service to take steps to designate the Black River as a National Natural Landmark.

Refugia. When I close my eyes, I can still feel the velvet air lit with ethereal green and hear the Prothonotary Warbler’s clarion tweet tweet tweet tweet! Messenger. Teller of stories of this climate refugia- bald cypress filtering waters, sequestering carbon, and weaving an intricate fabric of thousands upon thousands of beings we have yet to comprehend.

Isn’t it time we fell to our knees? Praise the ancient ones. Shore up each other. Entwine our roots. Act on behalf of all our kin.

#

More Resources

The Ancient Bald Cypress Consortium

Ghost Forests (Joel Bourne’s article in National Geographic September 2023, subscribers only for digital)

Congaree National Park (featured in the Old-Growth Network)

Take Action! Support southeastern forest environmental groups working to end the devastating clearcutting of forests for the wood pellet industry –part of the dirty biomass industry (greenwashing at its worst and now threatening Pacific Northwest Forests). Those groups include the Dogwood Alliance and Southern Environmental Law Center. (See my related blogs– A Kingfisher Runs Through It and Stand up for Forests of the Southeast.)

Note–All photos taken by Marina Richie unless otherwise noted-location services turned off to respect the privacy and security of these precious trees.