Opal Creek Ancient Forest: Abundance After Wildfire

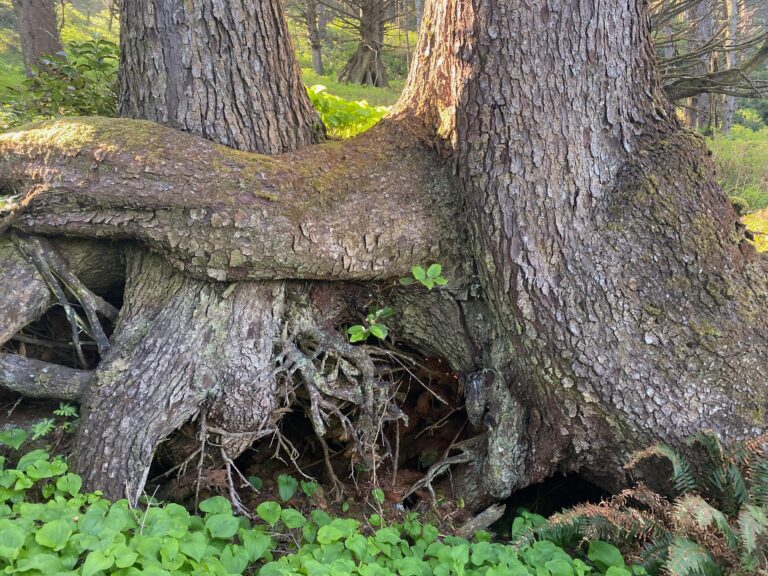

The word “abundance” is on the tip of our sweetened tongues. Melt-in-your-mouth blackberries burst from the native vines twining along the ground. Lazuli Buntings are singing their hearts out in the renewal. The buntings nest in the sunny emerald thickets beneath charcoal giant firs, hemlocks, and cedars. Butterflies flash patterned wings. Fireweed blazes purple against the black bark of a tree too wide to hug. Bigleaf maples extend wide leafy hands. Bracken ferns soften our way. Knee-high Douglas-fir and western hemlock seedlings shine with bright green new needles.

It’s the last weekend in June, and almost five years since the Beachie Creek Wildfire raced through the Opal Creek Wilderness, the revered Opal Pool, and Jawbone Flats. I’m among the lucky ten people who signed up with the Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center as the first public group to enter and spend the night in the one cabin that did not burn down.

Some in our group have vivid and cherished memories of sunlight filtering through layers of conifer branches to light upon deep mosses, of the great living trees cloaked in lichen, and the sylvan magic of Opal Creek’s waterfalls and pools. Others, like me, have more distant memories. We are all ready to open our senses to a wild forest renewal without human intervention. And there’s trepidation as well. How will it all feel?

Rewind to the fateful day of September 7th, 2020. A once small wildfire in the Opal Creek Wilderness whipped into a wild blaze. High heat, extremely dry conditions, and east winds fueled a fire that ripped along at a staggering rate of 2.77 acres per second. Winds gusting to 75 miles per hour knocked down powerlines on Highway 22 and sparked 13 new fires. Another wildfire called Lionhead merged with Beachie Creek and together burned 310,000 acres. Homes were lost. Four people died, including George Atiyeh, the passionate and articulate conservationist who fought long, hard, and successfully to protect his beloved giant groves of trees of Opal Creek from logging.

The sadness has eased. The forest is reviving with wisdom gained over the millennia. Even with climate change spurring mega-fires, there have always been severe wildfires within western forests. And even here where so many trees died, the fire hop-scotched over some. The living firs, hemlocks, and cedars are helping to seed the next generations. Higher up in the Opal Creek Wilderness beyond where we walked is still a large chunk of unburned older forest too.

Forty years ago in Opal Creek, I was fortunate to tag along on a hike with George Atiyeh, Dr. Jerry Franklin (the father of old-growth ecology), Tim Lillebo (big tree champion for Oregon Wild), and Brock Evans (famed eco-warrior of the Sierra Club and then Audubon). I remember clear deep pools, waterfalls, moss, mist, and the moist embrace of some of the biggest trees I’d ever seen in Oregon. At a naturalist pace, we reveled in all Jerry taught us. Throughout, there was strategizing on how to save Opal Creek as Wilderness and protect it forever from logging. It wasn’t easy. It never is. Brock Evans’ adage applies now more than ever: “Endless Pressure, Endlessly Applied.”

I never dreamed it would take me so long to come back or that there would be a wildfire–one for the centuries. What I’m most grateful for is the designation in 1996 of the Opal Creek Wilderness and Opal Creek Scenic Recreation Area. Those 34,000 acres of old growth are not gone. The ancient forest is still here in a new form, and will not be violated with “salvage” logging and roading that is extremely harmful to forest recovery–eroding hillsides, destroying the mycelial network in soils, and clearing the standing and fallen trees that are essential for new life—like birds!

We have a citizen science assignment to help with a bird richness study led by Jennifer Johns (biology professor at Chemeketa Community College ) and Megan Selvig ( programs director for Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center). Everywhere is bird song, yet the singers are elusive. We’re all using the Merlin App to record birds and compare notes.

Over the weekend, our group comes alive to birdsong and identification. A female MacGillivray’s Warbler pops up to scold us from a likely nest spot within a tangle of a downed tree. Hairy Woodpeckers tap for beetles in snags. Vaux’s Swifts arc high above us, hunting for flying insects above the Little North Santiam River carving through boulders once cloaked in moss and overhanging trees. The swifts find the highest concentration of prey near flowing water and very likely they are nesting in burned trees snapped off by winds and hollow. (See an earlier blog about migrating swifts roosting in chimneys.)

At dawn of our second day, the early risers walk from the cabin to the Opal Pool to help with the survey plots. This is where the fire hit hardest with high winds knocking down trees. The pool soon was choked with wood but is gradually clearing with natural spring flooding. It’s shocking to see, until I’m swept away in the spiral of the Swainson’s Thrush solo.

We learn the protocol of listening and watching for birds for ten minutes of silence at each plot. Most in the group are new to the Merlin App. We compare notes and revel in the music of MacGillivray Warblers, White-crowned Sparrows, Lazuli Buntings, Western Tanagers, Western Wood Pewees, and Cedar Waxwings.

On our hike out, we help with more plots. We mingle, chat, and find more ways our lives are surprisingly intertwined from who we know, where we are from, and our love of nature. In silent observation, we revel in birds–finding the highest diversity in the severe burn of the Hewitt Grove, harboring some of the forest’s biggest trees.

Through the lens of birds, we’re coming to know a forest bustling and bursting with life. When we taste a sun-warmed blackberry or thimbleberry, we edge closer to what sustains us. The rush of the Little North Fork Santiam carving through rocks courses through the water in our bodies. There’s a renewal going on among us, too. We have left the outside world for two precious days of gratitude and hope.

Before we head back to our other lives, we press our hands together in a circle and give out our cheer– Lazuli (Laz-you-lye)!

(Note- I admit to sharing the pronunciation for Lazuli Bunting–one that I’d learned from western birders who set me straight).

Thank you to Opal Creek Ancient Forest Center –and to the wonderful staff that made our trip possible Please consider a donation! Note that Opal Creek remains closed to the public, with the exception of the specific guided trips that filled quickly this year.

Please also see my June 27 substack post–what’s at stake for our remaining wilds and a call to action. Thank you. Roadless Forever: Save the Heart of Our Public Lands.