Song Sparrow Sings the Pacific Ocean

I have a confession. There is no hardship in this brief tale of attending to the inventive compositions of a male Song Sparrow. No shivering and numb fingers, even when the clouds tossed hailstones upon my damp hair. Wes and I had come to join good friends at a beach house near Yachats and here it comes—my full admission of luxury. For three mornings, I wrote journal entries in the hot tub (between rain squalls).

There, my attention turned to the soloist among the salal at the shifting edge between the Pacific and the shore, nibbled and torn by hungry storms. On the first morning of the decadent watch under a chill wind and breezing clouds, I jotted down several mnemonics, including Praise Praise cheeeEEER day-day-day.

Poised on a leafless vertical twig of a bush within the salal hedge separating bird from beach, the sparrow opened his conical beak and unrolled masterful phrases that rose and fell as the waves crested, broke, and sifted the sands.

The music tasted like a steaming cup of French roast coffee softened in cream with a hint of maple syrup. Bittersweet. A spoon stirring longing. The notes were as restless as the creamy frothy waves—not all rolling in with the same velocity or reach, yet always rhythmic and often repeated.

On another morning, I attempted to convey his phrases in multiple ways. I started with a technique learned from teaching children to create song maps (years ago when I lived in Missoula). The teachers applauded this activity for second graders, because the key ingredient was listening without saying a word. No racing around and hollering.

Each child would find a separate spot among the spring greening of cottonwoods and meadows by the Bitterroot River at Maclay Flat. The assignment was to draw a simple map of the surroundings and then add the sounds of the birds where the student heard them—high in a tree, over by the river, deep in the brush. The kids drew squiggles, dots, spirals, curls, and repeated lines of varying lengths as a way to translate, say, the drumming of a woodpecker or the witchety witchety witchety of a Common Yellowthroat warbler.

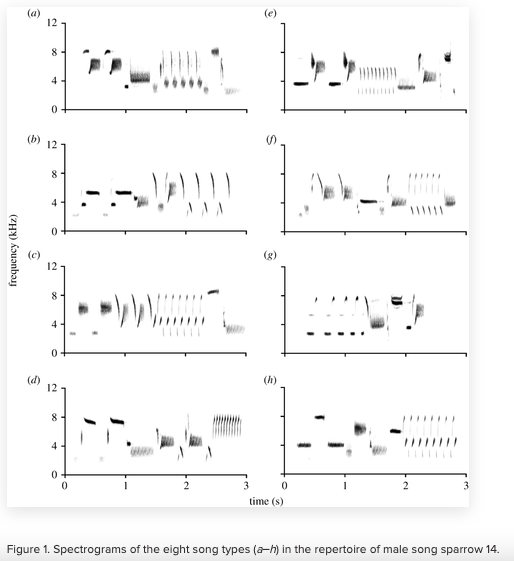

Names didn’t matter–only the pencil moving on a map with a freedom to express without words. What the students drew proved similar to spectrograms you can watch when using the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Merlin App, which records and identifies bird calls, chips, and songs.

After a few minutes passed, we’d gather and compare maps—noting where the songs clustered in the richest parts of the floodplain. To my delight, some of the children knew the names of multiple birds. What I hoped they might take away from this activity (not one I’d made up) was the gift of quieting human voices to hear wild music. I liked to believe some would keep listening as they grew into adults. I hoped they would notice where the bird chorus is weakening, and they would care enough to act.

Continuing the luxuriant watch, I tried writing a certain tune as words angling up and descending across the blank page—See! See! See! Cheerily-cheerily chhhhh…..eeer… bew.. now! Now! Now! I penned quarter notes and riffs of sixteenth notes. Always, I watched the streaked brown bird with the dot on his chest as his head tilted back and beak scissored the petulant sky. Sometimes, he ended on a lingering question. I caught hints of skipping ropes, insect-like buzzes, and chirping claps. I tried to catch the nuance of what was repeated and what was new.

Song Sparrows are virtuosos. In a 2022 study, ornithologists set up their recording gear within a northwest Pennsylvania woods and listened for five hours a day until they had collected suites of the short songs from 30 males. While prior studies showed the sparrows singing a dozen distinct riffs and often repeating the same one several times, the researchers wondered if the birds shuffled the order with intention. They did indeed! What a bird sang in the present depended on what he’d chosen a half hour earlier. Also, if he was particularly entranced by a certain phrasing and repeated the tune multiple times, he’d wait longer to come back to that one.

The study showed song sparrows have a rare talent called “long-distance dependencies.” So good is their recall that they blew the previous avian record holders out of the water. Canaries can manipulate five to ten seconds of song information, while Song Sparrows can rearrange a half-hour’s worth–a 360 times larger memory capacity.

The lone sparrow belting out blossoms of melody from the salal was not always alone. Once, I heard another singer in the distance. Another time, he lifted into the air and flurried off with…a female? Soon he was back to the favored perch only a dozen feet away—this troubadour of the Pacific edge.

The music felt as textured as a gull’s feathery wing, as precise as a flap, and as easy as a glide. The ocean thrummed like a goddess stretching in a dream as her toes flexed on wide shallow sands. Winds strummed the storm clouds thickening, parting, and lowering. When hail ricocheted off salal leaves and my shoulders, too, the sparrow ducked under cover. Clambering out of the hot tub, wrapping a towel around my dripping wet swimsuit, I felt the pelting notes upon my skin. At last, the Song Sparrow’s theme and variations had found a way in. No need for a pen, a piece of paper, or even a word.

#

For a related blog I wrote, see Pacific Wren: Virtuoso of Spring in the Ancient Forest

For a book filled with interpreting bird songs and written by a musician, I recommend a book I read recently, Call of the Kingfisher: Bright Sights and Birdsong in a Year by the River, by Nick Penny.

And–I have news! Halcyon Journey, In Search of the Belted Kingfisher has won the 2024 Burroughs Medal for distinguished natural history writing. I am humbled, honored, and amazed. I do feel I owe the award to the kingfisher! See also this post from my wonderful publisher, Oregon State University Press.