sauntering with thoreau in central oregon

“I must walk toward Oregon, and not toward Europe.”– Henry David Thoreau, “Walking”

The sun waves a casual wand, casting aureate rays on summer’s fading green. In the Turquoise Forest of ponderosas at the edge of a seven-thousand-year-old lava flow, I follow the slant of October light to a wax currant bush rooted in a sniff of soil. Ragged rocks crest like petrified waves. Backlit frilly leaves coin the afternoon in gold. The sun guides my footsteps. I am not in a hurry. I am envoking Henry David Thoreau. There can be no better healing than sauntering in a sliver of wilds, with anxiety of autocracy and environmental disaster slipping away for now.

I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements. – Thoreau, “Walking”

I choose the trail-less way of curiosity over destination, the Henry David Thoreau way. No matter that he sauntered 175 years ago and three thousand miles away in Concord, my home during high school years. After he penned his essay “Walking,” his spirit is everywhere— in the way he wrote of sauntering: “Some, however, would derive the word from sans terre without land or a home, which, therefore, in the good sense, will mean, having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere.”

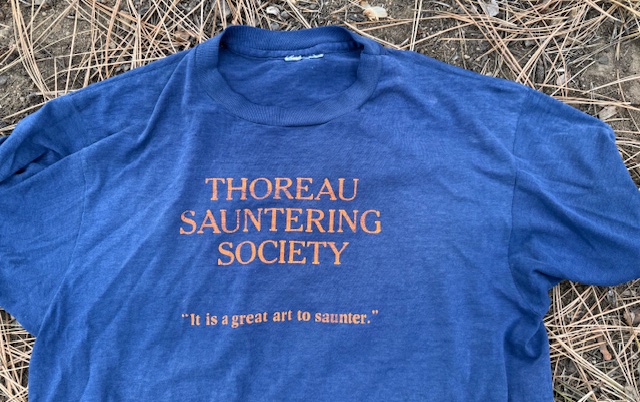

I still wear my father’s soft, thinning tee-shirt with the words etched in mottled pumpkin on blue: THOREAU SAUNTERING SOCIETY ….”It is a great art to saunter.” My Dad wore that shirt for years–hiking, backpacking, and sauntering. After his death from cancer at 70 in 2002, my mother gave me the shirt. The lettering, I notice, is the same shade of orange as the ponderosa pines, only those that are at least a century old. I wish I could bury my nose in the cracks of letters and breathe in scents of my father like I inhale vanillla from the bark of the wise trees.

Always, I walk to the Grandmother Tree, the oldest, tallest, widest, and straightest ponderosa there, and growing at lava’s edge, where mighty branches arc down to the rocks like wings of birds. Often, I look straight up from the trunk high into her branches. Always, I’m noticing something new or not new but draws me like the sun to the currant.

Sometimes, I wish I could ascend the Grandmother Tree, like I climbed on ropes up a very tall Douglas-fir in the Andrews Forest with bird biologist Nina Ferrari. (See blog). From the base, I cannot know the upper canopies, the view, and the ways of birds. In Thoreau’s “Walking,” he wrote of climbing a tree and perspective change that reminds us of the marvels out of view. It’s like being near-sighted without corrective glasses, missing most of a forest’s three dimensions.

We hug the earth—how rarely we mount! Methinks we might elevate ourselves a little more. We might climb a tree, at least. – Thoreau, “Walking”

On this warming day that began below freezing, I turn my limited lens upward to a focus on a perfect round nest hole fresh from this past season and not in the trunk, but in a thick dangling branch. Flickers found the dead limb among the living. Birds like sun rays are always pointing me to see anew, especially to value the dying, dead, dense, twisted, knotted, charred, and all that might seem askew and akimbo to those who perceive beauty in what is clipped, pruned, tidied, straightened, and ordered.

I stretch out on my back on ashy soil by manzanitas below Grandmother Tree in a sunny spot among shadows and look to a sky that is sapphire with wispy clouds. I note two Steller’s Jays on the chase, listening to their raspy squawks. Wondering about bird language. To “saunter” is to embrace being idle for awhile. Loosen. Let go of the turmoil of living in America in dire times. Breathe the breath of the ancient one. Soften into the wildness where we belong–not on pavement, cement, or any of the industries of our demise.

I would not have every man nor every part of a man cultivated, any more than I would have every acre of earth cultivated: part will be tillage, but the greater part will be meadow and forest, not only serving an immediate use, but preparing a mould against a distant future, by the annual decay of the vegetation which it supports. – Thoreau, “Walking”

Brushing off pine needles, I wander with the sun directing me to brilliant yellows and orange leaves. On my way to Scouler’s Willow, I clamber through brushy manzanitas with succulent evergreen foliage. I run my hand along polished branches twining burnt umber and driftwood gray. The living and dead in companionship. I’m growing older, and ponder whether I’m taking more notice of nature’s way of afterlife.

Ahead is a thatch of stalks streaking skyward. A lone raven flaps over deep time clefted in basalt. Willow beckons. She is like a water witch with a hundred broomsticks held upright. Presiding over lava’s last gasp, Scouler’s Willow is wise in the ways of living with less. Roots tendril into crevices, sipping not gulping. She holds her perished limbs close, gentling all that is brittle, cracked, and broken. Her oval leaves burst in frowsy flurries. I know what Thoreau meant about nature directing our steps if we are attentive, unhurried, and without destination.

What is it that makes it so hard sometimes to determine whither we will walk? I believe that there is a subtle magnetism in Nature, which, if we unconsciously yield to it, will direct us aright. It is not indifferent to us which way we walk. — Thoreau, “Walking”

I wonder about the age of Scouler’s Willow, wide enough to be a thatched dwelling, yet impenetrable. I only see this kind of willow at the lava’s edge, and not in all places. Often, songbirds cluster. Likely, small animals find refuge within thicketed stems. I’m drawn just as much to the gray, straight-up “hair” of the stalks as I am to the changing colors of leaves, the hues of Evening Grosbeak, Yellow Warbler, and Northern Oriole. The airy, bubbled lava rocks are often loose. I tread with care. Peer into the branches where I am far too big to enter. I’d have to be like sagebrush lizards, pine chipmunks, voles, mice, or tiny pikas that surprisingly live in these lava fields of Newberry National Volcanic Monument.

The willow has the rugged qualities of the Monument’s thousands of acres of lava basalt, pumice, and ash. Far from barren, the roadless wilds bear twisted junipers and pines, tiny canyons of collapsed lava tubes with moss, ferns, and wildflowers, and kipukas–the Hawaiian word for the islands left when lava flowed around obstacles. To saunter takes a careful step, a willingness to go around, to test footing, and to give up our bipedal way at times and scramble on all fours.

Thoreau did not know lava or the Scouler’s Willow, but he did know swamps that he found far from “dismal.” Our family’s home in Concord backed up to hardwoods where I often sauntered (in the mid-70s in high school) with Thoreau’s journal entries and found Gowing’s Swamp, a quaking bog of sphagnum moss over layers of peat where tamaracks and black spruce grow. I could only get there by wading. I thought only Thoreau and I knew of this place. But today the swamp is protected, fortunately, although now on the map. It’s better to be known and saved, then overlooked and demolished.

When I would recreate myself, I seek the darkest wood, the thickest and most interminable and, to the citizen, most dismal, swamp. I enter a swamp as a sacred place,—a sanctum sanctorum. There is the strength, the marrow, of Nature. – Thoreau, Walking

I have walked only a couple of miles in the Turquoise Forest compared to Thoreau’s four hours a day, where he might cover ten to fifteen. When he wrote of that era so long ago in the mid-1800s, the Concord countryside was far more expansive. Reading his writings, I feel sorrow for all that is lost and today’s frenzied expansions of Bend, my community. Every day, more forests, sagebrush, juniper, and bunchgrass are razed for housing without regard to wildlife, ecology, and our shared need for water in a dry land.

I can easily walk ten, fifteen, twenty, any number of miles, commencing at my own door, without going by any house, without crossing a road except where the fox and the mink do: first along by the river, and then the brook, and then the meadow and the wood-side. There are square miles in my vicinity which have no inhabitant. – Thoreau, “Walking”

Even now in the developing West, we have our saving grace–millions of acres of public lands. The Turquoise Forest is on the Deschutes National Forest. As I revisit Thoreau’s “Walking,” I know he is calling us in spirit to protect our public lands from all who would sell them off, all who would deem the only values as extractive–logging, mining, and grazing, and all who treat our public lands as profit for the wealthy.

In my sliver of escape, I let all those terrible threats retreat for a time. When I ambled back home, I delved into doing my small part as a writer, environmentalist, and bird-friendly yard tender.

On that note, I’ll end with the most famous quote from Thoreau’s essay “Walking” and one my father taught me at a young age.

..in Wildness is the preservation of the World.

I love the beautiful Massachusetts woods!