A Reverence of Crows, A Tree’s Last Stand

I’m with photographer Nancy Floyd in downtown Bend on Congress Street, a sleepy, tree-lined street with stately homes dating back to the early 1900s. Nancy and I connected over her long-term photography project “For the Love of Trees” and became immediate friends. Her subject on this day is a grand ponderosa pine lofting above all others. The upper trunk arcs slightly to the northwest. The long branches swirl on all sides like arms akimbo. Every needle on the tree is dead. Only recently did the great tree succumb. Across the street is the stump of a smaller companion cut down several years earlier.

Pygmy nuthatches, tiny, agile, and squeaky as mice, flit among the limbs as I watch Nancy see the tree through her camera lens– a way of perception that will change mine. I notice how the camera becomes an extension of her body. She is practiced, focused, and at once deliberate and spontaneous as light shifts and a tree branch shadow curves over the plated bark. Before I arrived, she photographed a downy woodpecker on the crook of a limb. As I’m taking notes on my clipboard and she is clicking photos, something else happens.

We begin to meet curious neighbors. We hear the story of the coming of the crows last fall to the dying tree. The birds streamed in before dusk to fill the upper half of the tree–about two hundred roosting in the upper half of the tree that had begun to die from the top down. They’d never seen crows like this before on their street and never in that tree.

One neighbor said she had been sending silent messages of love to the struggling ponderosa and wondered if the crows had answered. In mornings, she would walk beneath the tree and pick up a feather or two in gratitude. I saw the other resident nodding.

“It felt like a reverence of crows,” he said. I noticed then how many songbirds had gathered as we clustered not far from the great tree on a mild end of January day of sun and clouds. Cedar waxwings gave their soft high-pitched seet seet calls. There were robins, flickers, chickadees, finches, and nuthatches. We felt ringed in their music as we felt a kinship– a love of trees.

The days are numbered for this tree to remain standing and life-giving to woodpeckers, owls, and all who would come here. The tree will be cut down and the street, houses, and people will be safer and neighbors will feel the loss. The same man who spoke of the reverence of crows had said this earlier, “If I lose my house to fire or something else I can rebuild, but if a 100-year-old or more tree falls I can’t replace that.”

Gazing up at the elder tree filled with personality even in death, I return to a favorite quote from Rachel Carson’s Sense of Wonder. “What if I had never seen this before? What if I knew I would never see it again?”

Soon, I will never see this queen of a ponderosa again with the full skirt of lively branches. I will keep the vision of this tree in my heart, too. I can understand why the neighbors who have become intimate with their tree friend are mourning.

Why did the tree die? Why did the crows come to roost there in October and November? How can one great tree become a portal to the wild forests and lead to more people caring about threats from logging? Could they care more about the fate of dead trees in a wild setting that are so critical to be left standing for woodpeckers, owls, carbon, and the cycling of a forest? So many questions are flying into the roost from this one outing.

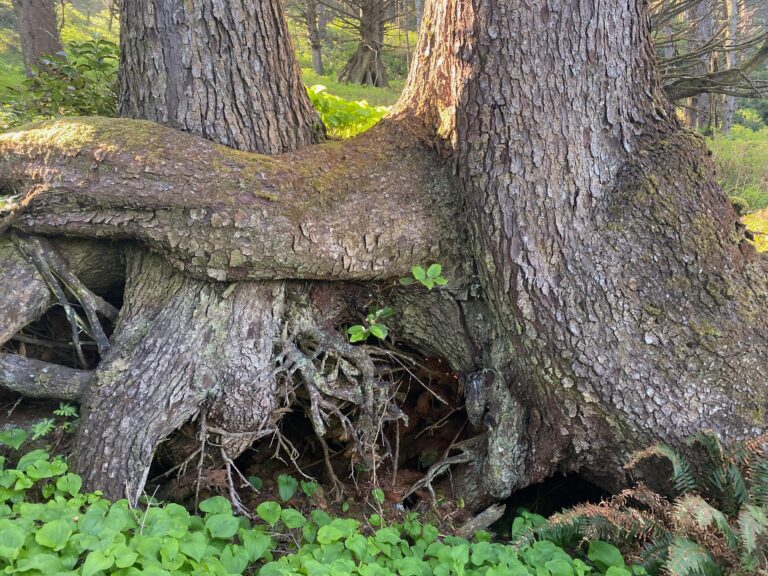

While on the surface it might appear the centuries-old pine died strictly from lack of water, the tree’s fate was likely set long ago when the city widened the street around the pine–sparing the tree initially. When I consulted an arborist and sent a photo, he pointed to the street almost touching the tree and pavement suffocating about 70 percent of the drip line (the outer edge of branches where rain falls and soaks in to feed roots that extend far from the trunk). Paving compacts the soil and damages roots that can lead to pathogens entering through the wounds. Over time, the tree could not uptake enough water and nutrients to survive. While more watering likely would have helped, it would not have saved this vulnerable tree from what arborists call a “spiral of decline.”

Only a couple blocks away is Drake Park. There I grieve the recent cutting down of a historic ponderosa pine more than two hundred years old. The why of the tree death was clear. The Bend Parks Department built a new paved wide bike path next to the tree and severely damaged the roots. I had joined a group of women in February of 2020 protesting the plan to cut down up to 65 trees for the new path by Mirror Pond. We held a green ribbon protest, gained media attention, and saved some of the trees. “Don’t cut me down, go around” was our statement on the ribbons. But here’s the thing–you have to go way around and definitely not cut deep down through the roots. (See photos at end of blog of before/after for this tree that grew for centuries until a new bike path became more important).

How much room are we willing to give to keep big trees standing that give so much to us every day? Shade and coolness in the heat dome of climate-induced extreme heat. Carbon capture and storage–far greater than younger trees. Havens for birds that are messengers we should heed.

Why did the crows come to roost? Some questions are best left to the heart. I like to think of the neighbor walking to the tree in mornings to pick up feathers as she gazed upward into the whorl of branches. Perhaps the crows have something to tell us about big elder trees and how to show our love for them not just in our neighborhoods but everywhere. We also ought to honor losses. Never forget.

Through Nancy’s creative lens, this ponderosa will live on in photography. With every click, she teaches us the meaning of the word “reverence.” There are lessons, too, in the power of neighbors and community coming together for their love of trees–and to take greater actions no matter how difficult the times. Look around the place you live. What do you care deeply about? What will you do to show and share your love? Isn’t it past time we paid attention to the intelligence of crows and wisdom of ancient trees?

See my latest substack post , I Care Deeply About, How to Take Back Our Power.

Its always so sad to see

big old trees die and even more

so when it was human caused. At least in nature it could have been great habitat for decades more as a snag then a log. So many large old pines are dying now near where I live in the Front Range where the cause is long term drought and climate change which is even worse

since its much harder to fix than simply improving planning of roads and trails. So interesting about the crows. A murder of crows as they say.

Thank you. I appreciate you bringing up what a great snag and then a log that tree would have made if not on a street. I worry, too, about large pines in trouble from long-term climate change. What’s most important is to keep every big and large ponderosa standing–they are the water keepers–able to access the aquifer with deeper roots and bring it to the surface to benefit the smaller trees. But as we know, the huge elephant in the room is burning fossil fuels and the need to stop!

As Boise explodes with growth we sometimes save valuable old native trees even in the city of trees it does not always happen. We have parts of the green belt that moved far away from roots but many more sidewalks and paths that did not. Some of the trees lost were not native and some were some were replaced and some were not. But as you noted the large old natives replaced will not become true replacements in my lifetime.

I was thinking about the habitat created by snags and even downed trees when I was climbing over a downed tree on my last birding outing on the Boise River below the diversion dam (for the New York Canal). On that cold windy day I did not see insects and passerines pursing them but I had in the past on that fallen tree but I have in the past.

After I got over the downed tree and made my way accross the low water river rocks to a favorite winter spot to start an e bird list I encountered 5 adult Bald Eagles in the air at once and an immature one across the river perched in a scraggly old mature Cottonwood.

I only found one Belted Kingfisher on this birding outing but the number of eagles and winter water fowl was fantastic along one of my favorite riparian corridors now protected as part of the Intermountain Bird Observatory 🙂

Thank you Ken for your naturalist observations and reminders of the values of snags, downed trees, and big old trees and how interconnected they are to birds, insects, and the health of an ecosystem–as is that beautiful Boise River of Kingfishers!

sometimes it feels like the way of the some of the human world is to put our feet bodily everywhere all at once. other lives die in the wake of our forward momentum. i am buoyed to read this story of a reverence of crows and arboreal portals and community care.

-gee from nyc

Thank you for your insight– so well articulated. How can we care for the lives of trees, birds, rivers, and more in the way of close friends and family? Living far more simply and taking far less is a good start. Even in this mayhem, anything we can do individually to be lighter on the Earth and in relationship matters.