Birds are Calling Us: Speak Up for Forests and their Native Plant Understory

This past Tuesday, I joined the weekly “Birding-by-Ear” walk in Sawyer Park by the Deschutes River in Bend. The morning sunshine showered us in the konk-la-rees of Red-winged Blackbirds, the clear single notes of Townsend’s Solitaires, and the melt-your-heart serenades of Song Sparrows. Our guide Dave Tracy has a magic touch. His ears are keen, his bird literacy deep, and his way of sharing a quiet and unassuming gift. Even as I immersed in bird song, I felt troubled by ongoing destruction of local bird habitat on the Deschutes National Forest in the name of reducing wildfire risk.

In a low but audible voice, Dave called out the birds he heard and pointed to locations. Between sightings, he became animated as he’d share invaluable tips. For example, Violet-Green and Tree Swallows can appear maddeningly similar, but in flight the Violet-Greens have shorter tails, white rumps, and more white on their faces. Sauntering on his familiar route, he’d pause at promising habitats, like tangles of dogwood, in bitterbrush, currants, juniper, pines, tall standing dead trees, and views of the river with rocks where a dipper might perch.

We entered into the rhythm of migratory songbirds flowing into the life-giving corridor on their way to nesting homes. Several Ruby-crowned Kinglets had just dropped in to enliven the thickets with frenetic motions. Smaller than a warbler, this ball of energy forages at high speed. Glimpses revealed a tell-tale white eye ring and wing bars on olive plumage. Seeing one kinglet is never enough. By looking closely at each one, we saw new behaviors, like a kinglet preening after a bath. We were rewarded by the rare sight of his ruby crown with feathers flashing and vanishing like an ephemeral gem.

The Ruby-crowned Kinglet possesses a mighty syrinx for such a diminutive songbird– unrolling whistled jumbled notes like an ode to all that is tangled, dense, and sheltering. Likely, many will fly hundreds of miles north to nest in Canada’s boreal forest, while others will breed closer in Oregon forests. In migration, thickets are essential. Kinglets build their nests high in tall trees that grow close together (not thinned and park-like forests).

On that morning, we witnessed many thicket lovers flitting among alder, dogwood, willow, and Oregon grape, including White-crowned and Golden-crowned Sparrows, California Quail, Pine Siskins, Lesser Goldfinches, and Song Sparrows. We looked to the ponderosa treetops to spot Townsend’s Solitaires and a departing Merlin falcon. Drumming Northern Flickers led us to life-giving dead trees. Violet-green Swallows wheeled in the azure sky snatching invisible insects. A few Bushtits clustered in junipers just above eye level. From the ponderosas, Pygmy Nuthatches nattered and chattered, their calls like flying chips of scattered sun rays.

Every bird has its place. Every layer matters. All is connected. The early pink blooms of manzanitas invite bees, butterflies, and untold insects. Birds forage for life-giving insects on emerging buds. To become a good birder, knowing habitats, timing, and relationships is as important as identification by song and sight.

CALLING BIRDERS TO ACT TO PROTECT FOREST HOMES FOR BIRDS

I’m calling birders to action on behalf of our threatened and vibrant forest understory –home to roosting and nesting birds, countless insect species, and critical for mule deer in winter for browsing shrubs.

The Deschutes National Forest is in the process of mowing, “masticating,” and tearing up miles upon miles of bird, pollinator, and mule deer native habitat as part of “fuels reduction” and “restoring historic conditions.” Thousands upon thousands of manzanitas, ceanothus, currants, and bitterbrush will never bloom this year, never shelter birds, and will instead be ground up into chips. The churned up ground is an invitation for invasive and highly flammable weeds and grasses to take root. Across the West, the Forest Service is carrying out logging and mowing–fueled by money from the Inflation Reduction Act for “wildfire mitigation.”

I received my information firsthand from speaking with a Forest Service fuels planner who explained to me why they are clearing 75 percent of the understory in project areas. More than 50,000 acres on the Deschutes National Forest are slated for “treatment” this year, which includes mowing, thinning (logging), and prescribed burns. The engines are revving–right during the springtime of bird migration, arrivals, courtships, and nesting season around the corner.

My call was specifically aimed at my alarm over seeing new flagging and paper signs on trees within a favorite dog-walking part of the national forest, not far from my home in Deschutes River Woods. I’ve come to know the mostly second-growth pine woods nestled against vast lava fields on four-mile loop hikes and cross-country wanders. Among the waves of ceanothus, manzanita, currants, and bitterbrush. I’ve listened to singing Fox Sparrows, Green-tailed Towhees, and Spotted Towhees. There’s a certain grove where a Pygmy Owl tends to perch and call in winter. In the ashy soils are many living creatures–even moles. After snowmelt and rain in spring, the understory and meadows bloom in penstemons, paintbrush, buckwheats, and sand lilies.

While the fuels planner expressed empathy for my concern about ground-nesting birds and pollinators, he told me that these pine forests are not supposed to have this level of brush. Reducing fuels is one goal, but so is an intention to try to turn back the clock. He also said by cutting down the native brush, they can then conduct prescribed burns without harming the smaller pines. He told me that leaving 25 percent is a nod to the nesting birds.

Is it possible to reset the clock to some predetermined historic condition before massive logging and suppressing fires? We’ve irrevocably changed our climate by burning fossil fuels. We’ve cut most of the forests, except for the refugia of remaining groves, roadless areas, and designated Wilderness.

Wouldn’t embracing the biodiversity of our beautiful manzanita, ceanothus, and bitterbrush be better? Wouldn’t it be conservative to conduct thoughtful field studies on ecological and wildfire relationships ? In a time when pollinators and all native insects are in great trouble, and North American birds have declined by more than 3 billion since 1970, we ought to protect every bit of habitat we can. With worrisome declines of mule deer, we should conserve the native shrubs they must eat for survival. Yes, fires will burn in some places, but these are plants adapted to fire’s renewal.

What About Staying Safe from Wildfire?

Whenever anyone hears the word “wildfire” in this heating-up world, there’s an element of understandable fear, even if we are aware that wildfires have long shaped many western forests. We might shrug our shoulders and think, “if this is what the Forest Service has to do to protect us from fire, then we have to accept the damage of cut-over and mowed forests.” But will these massive logging and mowing projects keep us safer? I worry about wildfires, too, as our summers grow hotter and dryer.

We must go straight to the cause of wildfires that are becoming so deadly to people and drastically cut fossil fuel emissions. We can’t log and mow our way out of the wildfire crisis. Like cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face, logging is adding more emissions and removing our best source of carbon-capture—our trees. The bigger and older the trees, the more carbon they store and for longer periods.

We know from recent wildfires that when there’s record-breaking heat, high winds, and drought, only autumn rains and snow will put them out. Many fires burn hottest over logged lands where wind-driven flames speed through opened up forest, often fueled by weedy understories. In contrast, they tend to slow down when entering cooler, lusher forests.

Do we try to stop a hurricane? Do we try to stop a tornado? It’s hubris to think we can “manage” forests to stop weather-driven wildfires across great grasslands, brush, and forests. As the film Elemental so clearly shows, the best course is to focus on the areas right around homes and structures. I’d like to see Congress redirect the massive amounts of funding given to federal land agencies to where it will make the most difference. For instance, tax breaks and other subsidies could incentivize homeowners in fire-prone areas to replace shingle roofs with metal and other upgrades. The more resilient houses are to wildfires, the safer our brave wildland firefighters will be as well.

A forest is far more than the trees. We are lucky in Central Oregon to live within the beauty of manzanitas, currants, bitterbrush, and ceanothus gracing our forests. Every spring and summer, I’m amazed by the exquisite timing of the blooms–not all at once, a parade of unfurling to sustain pollinators and birds. Manzanita is the early bloomer; the pink clusters of bell-like blossoms bright over snow patches in the forest. Already, I hear the bees humming and notice butterflies.

Birders! Nature lovers! Let’s campaign on behalf of birds. Educate ourselves. We know where birds take shelter, nest, and move throughout the day. We value complexity, tangles, thickets, density, dead and downed trees, and all that birds depend upon. We head to different elevational forests with their own fire regimes, tree species, and naturally dense groves to find birds that live there.

Courting Lincoln’s Sparrows sing sweet arias from mountainous forests with wet meadows and nest on the ground under shrubs.

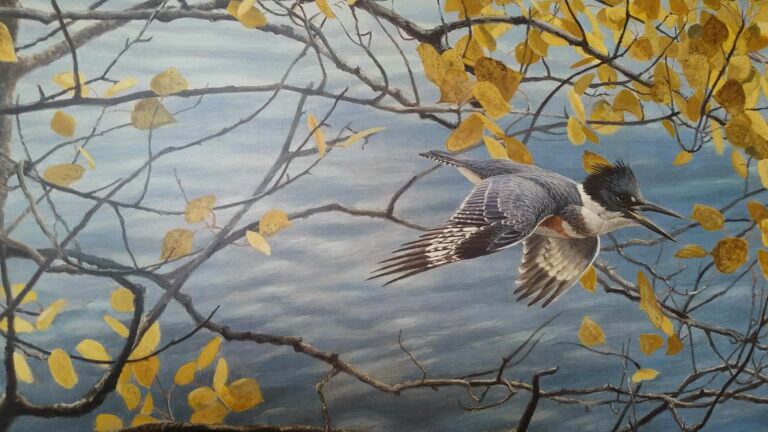

Varied Thrushes come to our yards in winter, but in summer flourish only in wet, dark, shady forests that are intact with ancient trees of many layers, ages, and with plentiful snags. They nest in the understory–choosing a small conifer to weave a cup composed of all that makes a forest whole–decaying wood, moss, and silky grasses.

To find Great Gray Owls–largest owl in North America–birders seek the forests now targeted for “thinning” and mowing. During the Christmas Bird Count, I was with a group in Sunriver walking through naturally thick lodgepole and fir forests not far from the river when a magnificent owl flew up from a small meadow. (For more on Great Gray Owls, see The Owl and the Mistletoe).

Now is the time for all of us to speak up for birds before their songs go silent in our forests. Will we watch the birds in our yards grow fewer and fewer, as logging and mowing turns their nesting homes to shambles? Will we no longer hear the muffled hoots of a Great Gray Owl?

Here are a few suggestions:

Get informed about what birds need in every season. A terrific online source is All About Birds, by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Join your local bird organization. Partake. Encourage advocacy as part of birding. Here in Bend, the East Cascades Audubon Society leads bird trips, conducts invaluable surveys, holds monthly meetings, and invites more people to fall in love with birds.

EBird is a powerful App. All the entries people make add up to vital citizen science documenting species, numbers, and locations. Match those with planned logging and mowing and bring the birds to the attention of the Forest Service. The Merlin App has opened up the world of bird identification through sound recordings. Use this information to stand up for birds–with hard data to support you.

Contact your local Forest Service office–find out what’s being planned for “management” and get involved. Pick up the phone. Stop by. Be courteous, ask questions, and share what you know about bird habitat. Ask to be informed ahead of time, and see if you might even volunteer to do field surveys as birders and naturalists.

Support environmental groups who are defending our national forests from damaging logging and putting forward exciting positive alternatives like the Climate Forest Campaign. Write letters when there are calls for action. Apply your personal love and knowledge of birds and nature. Write letters to the editor and to congressional representatives as well.

Keep creating birding and wildlife-friendly yards filled with native plants. Find out ways to do that while still being firewise. Support your local native plant nursery. (WinterCreek is wonderful in Bend). Connect with pollinator groups. (Another great group in Bend is Pollinator Pathway). Join a Native Plant Society chapter (like Native Plant Society of Oregon, High Desert Chapter).

Keep attending, learning birds by their songs, and finding rejuvenation and healing in the presence of birds.

Thank you.