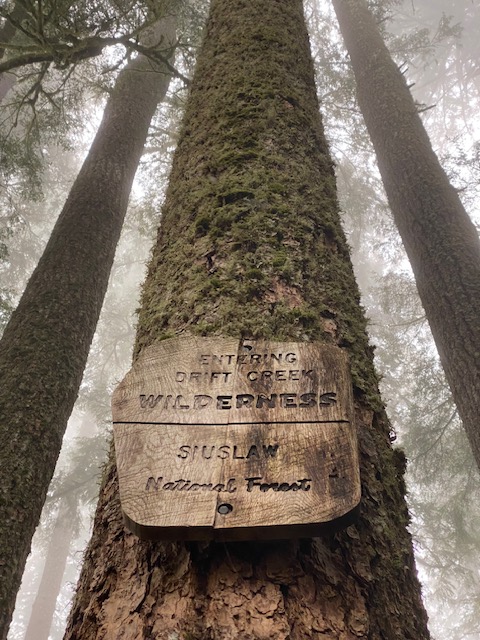

Drift Creek Wilderness– A Tribute

I’m drifting back in time in Drift Creek Wilderness, the largest remaining protected ancient forest in the Oregon Coast Range at 5800 acres. I’ve come here with my friend Sandra to camp at the Horse Creek Trailhead (about 14 miles inland from Ona Beach). Our plan is to hike to the creek–an eight-mile round trip. Memories swirl as I wander the trail with Sandra in the evening light–a prelude before the next day’s immersion, a day that would take us to the drama of chinook salmon spawning in clear waters over polished stones.

The slant of sun from the west splashes waves of light on tree trunks like ship masts in my favorite sea. Pileated woodpeckers drum a duet. Every step is a decision. Where to cast our gaze when drawn to dizzying heights and a miniature world at our feet? We’re often crouching to marvel at mushrooms with marvelous names like Slippery Jack and Pinewood Gingertail.

Drifting back to 1980… I’m a college student at the University of Oregon and teaching a class as an undergraduate called Oregon Wildlands, a course of the Survival Center (a dynamo student group taking on the world to save big trees, wild rivers, wildlands, and wildlife). The class was strong on field trips to endangered places. Drift Creek? Extremely threatened.

The loggers coveted the last great stands. The Forest Service sided with the loggers, as did most politicians. Timber ruled. We drove in vans from Corvallis to follow the winding Alsea Highway and then on rutted logging roads through vicious clearcuts–moonscapes of giant stumps, huge slash piles, and slumping hillsides. Perhaps the pain of that drive is one reason it’s taken this long to return.

But I’ll never forget what it was to step into the arms of the wild forest and breathe in the immensity of broad trunks, lofting trees living and dead; emerald shades of ferns, moss, huckleberries; fallen nurse trees sprouting western hemlock seedlings; and a sense that I’d entered a sanctum, a holy place.

I’m sad to say that driving to this northside trail brought back some of those nightmares. The closer we came to the protected wilds, the more fresh clearcuts and logging we encountered–on precipitous slopes and with giant slash piles, each with a scrap of black plastic on top (destined to be burned). It’s sobering and a reminder of the vital importance of Drift Creek Wilderness.

To celebrate what it took to protect this shining gem, a critical carbon and biodiversity reserve, I’m piecing the story together from queries to my friends–longtime environmentalist Andy Kerr and ecologist Paul Alaback. They were among the leaders of a decade-long (plus) fight for preservation ending in partial victory. The Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 included three coastal wilderness areas–Drift Creek, Cummins Creek, and Rock Creek. By then, I was living in northeast Oregon and advocating for wildlands there. Some made it in the 1984 final bill, including the North Fork John Day Wilderness, Monument Rock, and the expansion of the Strawberry Mountains Wilderness.

Before I turn to share a snippet of what I’m learning, I’ll drift forward to the next morning when Sandra and I wake to wafting mists and lowered clouds– ideal for a dreamy hike in a temperate rainforest.

The wilderness trail is spongy underfoot. We hike up a gentle uphill and descend gradually on a long ridge toward Drift Creek. Every step we take is an entry into another world. Every tree, fern, moss, lichen, sorrel, salmonberry, nurse log, fungi, banana slug, varied thrush, and Pacific wren is an individual with a story. Sandra calls the way of this path “the line of grace,” a term reflecting a passage hugging contours and flowing with the land rather than in opposition. Even the trail offers a lesson on how to live. The forest brims with interwoven wisdom.

I find out later from Paul and Andy that this northside trail was pivotal in the 1970s-80s campaign to save Drift Creek. Volunteers put many hours into maintenance after the Forest Service let it go. Without a trail, coastal forests are almost impassable. A key strategy for protection was to bring people to threatened wildlands. The adage “we protect what we love” is true.

Many whose footsteps might still echo here became ambassadors for Drift Creek–testifying at hearings, lobbying Congress, writing letters, and sharing their knowledge and passion. My original sojourn with the class was likely to the southside (the Harris Ranch trailhead)-also a beauty, but this trail passes by the most immense of Douglas-fir, western hemlock, western red cedar, and Sitka spruce. Some trees are seven feet in diameter.

What makes an ancient forest? Drift Creek Wilderness teaches the definition with every step. This is a forest of dynamic change over thousands of years. I see black fire scars on snags, sunny glades where trees have fallen perhaps from high wind, groves of younger trees and huge survivors of past fires–maybe 700 years old or more. While these tall carbon-storing giants often rise in columns holding up the sky, this is no cultivated park with widely spaced trees.

Trees grow and thrive as they will–straight, leaning, bowing, wrapping, or in clusters as if all sprouted from a Douglas squirrel midden. Firs mingle with hemlocks and cedars, but not randomly. Everywhere are the dead trees sheltering life in holes and hollows and the fallen trees nursing new life among the softest of moss beds.

Overstory. Midstory. Understory. Notice the word. Everything here is telling a story–and like the best of literature, the plots are interwoven in place and time. The characters are complex. But there is no ending, only a circling around–each circuit different, renewed, and astonishing.

From the horizontal plane of bipedal motion, it’s difficult to experience the three-dimensional world. The best Sandra and I can do is pause to scrutinize spider webs shimmering in droplets, feathery moss, deer and sword ferns, Oregon grape, evergreen huckleberry, lichens and fungi–to name a few. Or to stop and look up, up, and up with chins lifted to the high canopy.

Birds lift our attention to all levels of the wild forest. Each species seeks nooks, crannies, and havens at various levels. The more complex and tall the forest, the more choices birds have to find refuge–critical with the weather extremes of the climate crisis.

A Pacific wren darts from behind a wall of tipped-up roots of a fallen tree. The petite singer has gone quiet in late October. Another flutter of larger wings. A varied thrush flurries through the mist at eye-level –festive in a plumage of Halloween orange and black. Chestnut-backed chickadees converse in whispers at every level. We never see them. High above in the canopy, a string of bird notes like flickering lights almost illuminates what we cannot see in the fog. A flock of red crossbills seeks ripened cones. Ahead and below us, we hear the beckoning hush of Drift Creek.

We come at last to the spawning chinook salmon as a bald eagle lifts from a spruce limb and flies downstream. In one pool and riffle, we count five. I guess some are four-feet long, but it’s hard to tell when peering down from a steep bank. All are battered and losing their scales. They remind us of beaver-chewed sticks with little bark remaining. I think I can make out females with broader flat heads and males with hook jaws. Their colors are bruised purples and loden green. Motions vary from finning the currents facing upstream to sudden bolts forward or sideways. Then, there’s the wild splashing as a female wriggles sideways to hollow out a nest in the stones called a redd.

The salmon have come to the wilderness, where the knitted forest of big leaf maple, cedar, fir, and spruce shade and hold the banks in place. Imagine what it was a century ago–thousands upon thousands of salmon streaming toward their birthplaces for that final act of spawning and death. Salmon feeding and nourishing the forest. Abundance. Yet, to see even a handful on this day felt like witnessing a miracle. Sanctum.

As we hiked back up the “line of grace,” Sandra and I felt nourished, held, and uplifted. Leaning close to a mother tree, we listened. This heartbeat. This mycelial network underfoot. This one flicker of our lives and a friendship spanning miles and decades. Always recipriocal.

This Wilderness. This gratitude to the women and men who gave and gave of their time and energy to save Drift Creek.

And here, I’ll share a little of the story I’ve gleaned so far from Andy and Paul. Originally, the Forest Service inventoried 6,400 acres of roadless land–leaving out a lot of old growth. Later, the agency increased the acreage to 11,252 acres, but Congress stuck to the lower figure for the final designation as Wilderness. The good news from Andy is that most is still roadless in what is called late -successional reserve status under the Northwest Forest Plan.

Paul recalled being part of a small conservation group in Corvallis speaking up for Drift Creek in the 70s and 80s–and joined by the Sierra Club chapter and Oregon Wilderness Coalition (today’s Oregon Wild and where Andy worked out of Eugene). Paul and others gave slide slows, appealed timber sales, attended acrimonious hearings, and led field trips on the trail. Paul often teamed up with Bob Frenkel (geography professor and local Sierra Club leader) and Glenn Juday, whose PhD dissertation focused on the remaining old-growth forests of the Oregon coast range. Glenn and Paul spent countless weekends in Drift Creek documenting the old growth with the help of students–another key to raising awareness.

The politics were rough. Timber really did rule, and convincing Oregon’s congressional representatives and senators to include the ancient or old-growth forests in the Wilderness Bill was uphill all the way–to put it mildly. There were losses, but yes there were wins, too. It’s never been easy to save wild places. Yet, that’s exactly what we must continue to do wherever roadless areas remain.

Long live Wilderness with the big W!

#

Note–please contact me if you were part of saving Drift Creek Wilderness. I’d love to hear from you. And if I have the salmon part wrong, please set me straight.

For a description of this trail and directions, please see Chandra LeGue’s outstanding guidebook: Oregon’s Ancient Forests: A Hiking Guide.