The Dave Richie Tree Survived Hurricane Helene

Earlier this summer, I received an email from Josh Kelly of MountainTrue that resonated on a deep personal level:

Hi Marina, I accompanied the ATC crew to treat the trees at Moffett Laurel Botanical Area a couple of weeks ago. I was sad to see that Hurricane Helene hit the area with high winds. I estimate that about 20 treated ash trees were brought down, including some of the big ones. Fortunately, the Dave Richie tree survived, as did many other beautiful trees. The Dave Richie tree is in an exceptionally sheltered location, and it not only survived, but it is over 40″ in diameter now and has grown over an inch in diameter since we started treating it.

In June of 2019, I tagged along with Josh and the rest of the crew protecting ash trees within the Appalachian Trail corridor. Clambering off trail, we entered a verdant, tucked-away grove or “cove,” hosting rare plants and wildlife. Even the Moffett Laurel Botanical Area could not escape the invasive emerald ash borer marching up the east coast and killing millions of trees. None of us would have predicted a massive hurricane.

When we came to the grandest ash tree of all, Matt Drury of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) turned to me. “Let’s name this one the Dave Richie tree in honor of your Dad.” And so we did. Then, they got to work injecting insecticides. The hope? Over the years, the tree’s winged seeds would spin away on a breeze to land in good soil and grow. By then, the emerald ash borer would have moved far north, leaving the new trees in peace.

Matt and Josh never met my Dad. However, they knew of his leadership in conserving more than half a million acres of wildlands along the A.T. from Georgia to Maine when he served as the National Park Service A.T. manager in the 1970s and ’80s. I can think of no better tree to be named after my father — a forest lover, birder, naturalist, backpacker, environmentalist, anti-bureaucrat, and quiet visionary. He had a strong affiliation with that particular section of the A.T. for the spring warbler migration and wildflowers.

When Hurricane Helene slammed into the southern Appalachian Mountains with high winds and a deluge of rain in late September of 2024, I feared for the ash trees. Would the cove with the Dave Richie tree truly be a climate refugia, surviving catastrophes?

To give a sense of the beauty of the cove and the ecological role of endangered ash trees, here are excerpts from the piece I wrote for AT Journeys magazine (Suite of Life):

“Crouched among ferns by a sentinel white ash, Matt Drury from the ATC and Josh Kelly from MountainTrue are laser-focused on their task. MountainTrue is a nonprofit dedicated to the conservation of forests and waters in the southern Blue Ridge Mountains. Kelly serves as the group’s public lands biologist. Drury is ATC’s associate director of science and stewardship, out of Asheville, North Carolina. The two are professional partners who share a passion for their home forests.

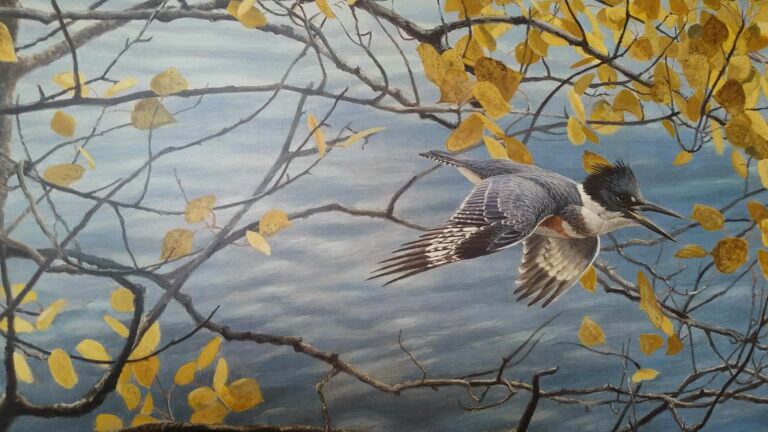

Above Drury and Kelly, a canopy of buckeye, sugar maple, basswood, yellow birch, and ash pattern the sky. A fluting song of a wood thrush filters through the leaf-struck sunlight. The understory brims with shade-loving plants, from the medicinal blue cohosh to mayapples. Within this haven of a Tennessee cove forest just off the A.T., life is both lush and fragile.

Along the A.T., primarily white ash and some green ash compose a vital three-to-five percent of shady forests. Hundreds of species of insects and spiders interact with ash and forty-four other species depend on them exclusively for survival. Wood frog tadpoles hatching in vernal pools grow larger, faster, and survive better when the leaves that fall into the water are from green ash. The trees host caterpillars so specialized to feed on them that some of the names contain the word “ash,” like the great ash sphinx moth. Songbirds like the scarlet tanager glean ash leaves for miniscule insects high up in the lofty tree canopy.

While every ash is important, the trees that dwell among a thriving forest community are entwined with a suite of life — from pygmy salamanders hunting insects up moss-cloaked tree trunks to black bear mothers raising cubs.”

Since 2016, the ATC and partners have treated some 1400 trees in the backcountry. They return every three years to inject them again. It’s difficult and heroic work. Sadly, fewer living trees remain after Hurricane Helene. The role of the Dave Richie tree is even more significant.

Some day, I want to return to the cove. I’ll linger and listen to the wisdom of the Dave Richie tree. If the mighty ash wants to know about my Dad, I think I will start with wonder. He was spellbound at every scale–from pounding waterfalls and see-forever summits to hovering hummingbirds and the shimmer of rainbow light on a spider’s orb web. I’d also let the tree in on a secret. My Dad never wanted to be in the limelight. He would likely prefer the tree be called by the true name known only to the ash. However, in his gracious way, he’d accept the naming if it made others happy.

My Dad left a legacy for all who hike the Appalachian Trail and for the ecosystems from Georgia to Maine. The namesake white ash is a legacy tree. What strikes me is another similarity– a style of humble leadership that ancient trees know and my father practiced. He lifted up others, gave credit generously, and followed the adage of Lao Tzu: “A leader is best when people barely know he exists, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: we did it ourselves.”

You might enjoy these related pieces I wrote:

Dave Richie and friends: Why the Appalachian Trail has Soul and Body today

The Big Bald Banding Station releases hope into the world

A few more bonus photos. The first one is post-Helene in the vicinity of the Dave Richie tree (from Josh Kelly) and the rest are from my 2019 field day.